Ah, April 1942, when DC Comics put out fewer comic books the entire month than it does these days in a single week! Yessir, DC released just 10 comic books 75 years ago this month. Although, in truth, DC was actually two separate companies at the time. There was Detective Comics, Inc. — the firm founded by printer Harry Donenfeld and his accountant Jack Liebowitz as collateral on the grandiose dreams of Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, which they used to force the Major out and acquire his comic book company, National Allied Publications — and there was All-American Publications, Donenfeld and Liebowitz’ partnership with comics industry pioneer M.C. Gaines, created under a similar arrangement to the deal that had not gone as well for the Major.

Ah, April 1942, when DC Comics put out fewer comic books the entire month than it does these days in a single week! Yessir, DC released just 10 comic books 75 years ago this month. Although, in truth, DC was actually two separate companies at the time. There was Detective Comics, Inc. — the firm founded by printer Harry Donenfeld and his accountant Jack Liebowitz as collateral on the grandiose dreams of Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, which they used to force the Major out and acquire his comic book company, National Allied Publications — and there was All-American Publications, Donenfeld and Liebowitz’ partnership with comics industry pioneer M.C. Gaines, created under a similar arrangement to the deal that had not gone as well for the Major.

Although they shared a printer in Donenfeld’s Donny Press, and a distributor in Donenfeld’s Independent News Company, and, most importantly, a book keeper in the form of Liebowitz, and even though they All-American titles often carried a “DC-Superman” cover brand, and borrowed from the D.C. Inc. stable of characters to round out its Justice Society roll call, All-American was an entirely separate company housed in entirely different editorial offices. The two companies would not merge until September 1946, when Gaines sold out his interest in All-American to Donenfeld and Liebowitz in order to go off and found his Educational Comics empire, and get killed in a freak motorboat accident.

So, of the 10 titles DC put out in April 1942, only six were truly its own: Action Comics, Adventure Comics, Batman, Detective Comics, More Fun Comics, and Star-Spangled Comics. The other four, All-American Comics, All-Star Comics, Flash Comics, and Sensation Comics, belonged to Gaines’ office.

But it’s primarily Sensation we want to talk about today, because the issue out 75 years ago this week just happens to be the first appearance of Wonder Woman’s magic lasso!

SENSATION COMICS #6

SENSATION COMICS #6

(on-sale Friday, April 10, 1942)

Today we tend to think of Wonder Woman’s golden lasso as an integral part of the character, as much so as her bullet-deflecting bracelets, her tiara, and her star-clad booty shorts. When DC revamped the character for the New 52 relaunch, you weren’t sure what they were going to do with the character, but you were pretty certain she was still going to have the lasso, at least.

And yet, it’s a late addition, not coming along until this, her eighth appearance.

The magic lasso — full actual name: The Magic Lasso of Aphrodite — was not originally able to make people tell the truth. Today it’s also known as The Lasso of Truth, but at first its only power was to make people do Wonder Woman’s bidding, or more correctly, it made people, men especially, submit to her charm. The whole tell the truth thing came about as an extension of that, as in, “I command you to tell me the truth!”

But then the lasso has always been able to so whatever a plot required of it. I remember how, on the old Lynda Carter TV series, it would only be long enough to loop around two or three times when hanging at her waist, but when she’d go do snare in a baddie, suddenly she’d he throwing 50 feet of rope!

An early promotional photo for Wonder Woman — they’re holding art for the cover of her second issue, which went on sale Oct. 21, 1942, and the photo first appeared on the inside cover of that issue with the heading, “Boys and girls, here are the men behind Wonder Woman” — shows, from left, creator William Moulton Marston, artist Harry G. Peter, editor Sheldon Mayer (a pretty good artist in his own right), and All-American line publisher M.C. Gaines. The photo was presumably taken in the AA offices, located at 225 Lafayette Street in New York City.

Wonder Woman was created by the king of kink, William Moulton Marston. An ardent feminist and committed bigamist (how’s that for a contradiction) Marston is credited by many sources as the inventor of the lie detector. This, the inference is often that the golden lasso was meant to be an allegory for this device. But among his many genuine talents, Marston was a gifted self promoter. What he actually did was develop a test for systolic blood pressure (that’s the top number in the modern blood pressure test), and that became a component in the polygraph machine actually invented by John Augustus Larson. Marston, using his doctorate in psychology, developed the DISC theory of dominance, inducement, submission, and compliance — another thing he popularized but did not create — in his 1928 book Emotions and Normal People. The DISC theory graphed folks based on their reaction to outside stimuli and Marston used it to promote his idea that masculinity and its ideal of pure freedom is, in fact, a violent state of anarchy, while the opposing feminine sensibility, which he called the “Love Allure,” produces an ideal state of submission to loving authority. You see where I’m getting at with the kink thing, right?

Martson was not only a booster of female power and an unbridled egoist, he was fairly prescient in terms of latching on to the public’s perception of the nascent comic book industry. Beating Fredric Wertham to the populist punch by about a decade, Marston had on interview published in the Oct. 25, 1940 issues of The Family Circle magazine, entitled “Don’t Laugh at the Comics.” The interview was conducted by his former student, and future second “wife,” Olive Byrne. In the article, Marston said that, rather than a delivery system for juvenile delinquency, he saw “great educational potential” in comics. Even at this time DC was concerned about parental reaction to its products, promoting in its pages a mostly made-up Editorial Board of Advisors that, it claimed, helped to guarantee its comics always contained good, wholesome entertainment. The Family Circle interview caught Gaines’ eye, and he hired Marston as an educational consultant for both the DC and All-American companies, presumably with the permission of partner Jack Liebowitz.

Martson was not only a booster of female power and an unbridled egoist, he was fairly prescient in terms of latching on to the public’s perception of the nascent comic book industry. Beating Fredric Wertham to the populist punch by about a decade, Marston had on interview published in the Oct. 25, 1940 issues of The Family Circle magazine, entitled “Don’t Laugh at the Comics.” The interview was conducted by his former student, and future second “wife,” Olive Byrne. In the article, Marston said that, rather than a delivery system for juvenile delinquency, he saw “great educational potential” in comics. Even at this time DC was concerned about parental reaction to its products, promoting in its pages a mostly made-up Editorial Board of Advisors that, it claimed, helped to guarantee its comics always contained good, wholesome entertainment. The Family Circle interview caught Gaines’ eye, and he hired Marston as an educational consultant for both the DC and All-American companies, presumably with the permission of partner Jack Liebowitz.

Once he had his foot in the door, Marston pitched Gaines on the idea of a new character who would represent female empowerment. He described the rationale behind Wonder Woman — his legal wife, Elizabeth Holloway Marston reportedly insisted the character be female — in a 1943 article in The American Scholar:

“Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power. Not wanting to be girls, they don’t want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are. Women’s strong qualities have become despised because of their weakness. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.”

So, in essence, Wonder Woman was a vehicle for promoting the ideal of passive submission in the form of a character who could kick ass and take names. Marston was nothing if not a bundle of contradictions.

Wonder Woman had her bracelets from the beginning, the legend being that they were inspired by jewelry favored by Olive Byrne, although Gaines and editor Sheldon Mayer rejected the character’s original name, “Suprema.” Although Marston essentially had two wives, he was allegedly the junior partner in the trio and it’s not surprising that a lasso became a much-used motif in his Wonder Woman comics. Even if Marston did originally sign the Wonder Woman stories as the work of “Charles Moulton,” using the middle names of himself and Gaines, he was oddly forthcoming in public in admitting that the lasso was part of what he was trying to accomplish with his comic book writing, to condition young readers toward a willingness to submit to “loving authority,” particularly female authority.

He would write in his American Scholar article, “Give them an alluring woman stronger than themselves to submit to, and they’ll be proud to become her willing slaves!”

In the Marston oeuvre, there’s hardly a story, or even a page, that goes by without someone getting tied up and his entire output (Marston died of cancer in 1947 at age 54) can be read as one big, long bondage fantasy.

In Sensation #6, the lasso is given to Wonder Woman as a prize for winning a roping competition against her fellow Amazons. In later versions of her origin, she’s have the lasso from the onset, but in this case returned to Themyscira (then known as Paradise Island) to win the totem, said to have been made from the metallic links of Aphrodite’s golden girdle. So, if we consider the bondage play Marston and his wives might have engaged in at home, to wield the lasso was not only a way to harness the power of Aphrodite, it was akin to being the Goddess of Love herself. Meanwhile, being tied in the rope was basically the same as being made to wear your dominatrix’ panties on your head. Seriously, early Wonder Woman comics were basically 50 Shade of Grey for Children.

In Sensation #6, the lasso is given to Wonder Woman as a prize for winning a roping competition against her fellow Amazons. In later versions of her origin, she’s have the lasso from the onset, but in this case returned to Themyscira (then known as Paradise Island) to win the totem, said to have been made from the metallic links of Aphrodite’s golden girdle. So, if we consider the bondage play Marston and his wives might have engaged in at home, to wield the lasso was not only a way to harness the power of Aphrodite, it was akin to being the Goddess of Love herself. Meanwhile, being tied in the rope was basically the same as being made to wear your dominatrix’ panties on your head. Seriously, early Wonder Woman comics were basically 50 Shade of Grey for Children.

The new book, Wonder Woman and Philosophy: The Amazonian Mystique, by Jacob Held and William Irwin, quotes Marston on the lasso from a 1942 Family Circle article entitled “Our women are our future.”

“Her magic lasso is merely a symbol of feminine charm, allure, oomph, attraction every woman uses that power on people of both sexes whom she wants to influence or control in any way. Instead of tossing a rope, the average woman tosses words, glances, gestures, laughter, and vivacious behavior. If her aim is accurate, she snares the attention of her would-be victim, man or woman, and proceeds to bind him or her with her charm. Woman’s charm is the one bond that can be made strong enough to hold a man against all logic, common sense, and counterattack.”

The fact that Wonder Woman could use the lasso to compel her captives to tell the truth did not make it a “Lasso of Truth,” a term never used by Marston, in the way we now think of it, as an instant lie detector. The idea was that to lie to someone is to assert a form of dominance over that person, something one could not do when submitting to authority.

In his 2004 book, Men of Tomorrow: Gangsters, Geeks, and the Birth of the Comic Book, Gerard Jones quotes Marston all but admitting that his Wonder Woman stories, and the use of the magic lasso in particular, was all part of the sex-training he was directing to young boys and girls.

“The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound… Only when the control of self by others is more pleasant than the unbound assertion of self in human relationships can we hope for a stable, peaceful human society… Giving to others, being controlled by them, submitting to other people cannot possibly be enjoyable without a strong erotic element.”

So, when you’re sitting in the theater a month from now, chomping on popcorn and watching Gal Galdot pop das Krauts on the head, maybe keep some of that in mind when she breaks out the magic lasso.

Also in this issue we find: The Black Pirate, by Sheldon Moldoff; Mr. Terrific by Charles Reizenstein and Harold Sharp; The Gay Ghost by Gardner Fox and Howard Purcell; Little Boy Blue by Batman co-creator Bill Finger and Jon L. Blummer; and Wildcat, by Finger and Irwin Hasen.

Most of those characters are familiar to modern readers. Little Boy Blue was a pubescent hero who was nobody’s sidekick. Instead he had sidekicks of his own in the form of two friends who fought by his side as The Blue Boys. The Gay Ghost was an actual ghost, the spirit of an 18th century Earl murdered by highwaymen, but he was goofy for girls, even in death.

The magic lasso debut makes this issue a little more valuable than the previous one. It goes for $4,000 in Near Mint, while #5 only commands $3,500. If you’re going for a lesser grade, expect to shell out $1,200 for a Fine condition copy, or $240 for Good.

Also published in 75 years ago by DC/All-American:

STAR-SPANGLED COMICS #9

STAR-SPANGLED COMICS #9

(on-sale Wednesday, April 8, 1942)

It’s just the third appearance of The Newsboy Legion, featuring The Guardian, in “The Rookie Takes the Rap,” by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. Then it’s the demoted Star-Spangled Kid, for whom this title had been created, in “Crime by the Chapter,” by Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel and Harold Sherman. Rounding out this issue are super-hero writer The Tarantula, drawn by Harold Sharp; humor strip Penniless Palmer, by R. L. Ross; Batman clones TNT and Dan the Dyna-Mite, by Aquaman co-creator Paul Norris; and Robotman, also written by Siegel, with art by the great Paul Cassidy.

This issue currently books at $2,600 in Near Mint, with Fine condition copies going for $780 and Good trading at $180.

Robotman and Tarantula are probably best known to modern readers, insomuch as 35 years ago is modern, as members of the All-Star Squadron. Dyna-Mite would be revived during the same time period as a member of the Young All-Stars. None have been seen in the post-New 52 era (at least that I know of). Penniless, a non-costumed private investigator would last in Star-Spangled all the way until #77 (on-sale Dec. 5, 1947), and even warrant a second feature in all 23 issues of All Funny Comics (including the cover to #1), though March 3, 1948, before fading into comic book limbo.

Star-Spangled would become a showcase for Robin with #65 (out on Dec. 13, 1946), although he would get supplanted as cover feature by Tomahawk with #96 (July 6, 1949), who would give way to The Ghost Breaker, Doctor Thirteen, with #122 (Sept. 14, 1951). The title would then finish out its run #131-133 as Star-Spangled War Stories. That title would continue, but renumber with its fourth outing (on Oct. 1, 1952) to #3, for some strange reason that probably has to do with the U.S. Postal Service and rules for second class mailing permits.

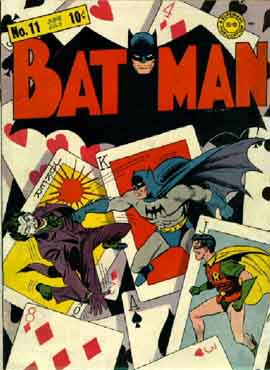

BATMAN #11

BATMAN #11

(on-sale Wednesday, April 15, 1942)

DC had Superman, of course, but it and Batman were bi-monthly titles at this time, and April was an off month for the Man of Steel.

This Bat-Issue marks the 11th appearance of The Joker, but just his second cover showing, after Detective Comics #62 (out on Feb. 25, 1942). The untitled story, sometimes called, “The Joker’s Advertising Campaign,” is written by Bill Finger and drawn by Bob Kane and Jerry Robinson — or, more likely, Jerry Robinson and Bob Kane. The same team handles three other stories in this issue, one of which, “Four Birds of a Feather,” features the third appearance of The Penguin. A fourth story in this issue is by the same art team, but with Edmund Hamilton at the typewriter. The villains in the other two stories, gangsters Joe Dolan and Muscles Malone, never warranted a second showing.

Still, with an early Joker cover (and a fairly iconic one at that), along with a nestling appearance of Penguin, expect to shell out a hefty $19,000 for a raw, unslabbed Near Mint copy of this issue. But have no fear, you can probably manage a Fine graded issue at $5,700 — or maybe a beater in Good for $1,330. Good luck!

Batman, of course, is still around, although it’s twice restarted its numbering. By my calculation, if it has never done that, and if we count zero, million, and 23-point issues, Batman’s next issue, out on April 19, 2017, would be #794. You think DC will revert to legacy numbering for #800?

FLASH COMICS #30

FLASH COMICS #30

(on-sale Wednesday, April 15, 1942)

The villain on the cover of this issue, who went by the name of The Grey Guardsman, has made no further appearances I know of. Still, his gimmick is pretty neat, and seems like the kind of thing the CW Flash show might successfully co-opt. It’s a ray that makes The Flash unquenchably curious, allowing GG and his gang to rob Keystone blind while The Flash speeds off on one wild goose chase after another, hunting down irrelevant answers to immaterial questions. “The Affair of the Curiosity Ray” is written by Gardner Fox and drawn by E.E. Hibbard and Harold Sharp.

Also in this issue we find Johnny Thunder, by John B. Wentworth and Stan Aschmeler; Chost Patrol, by Emanuel Demby and Frank Harry; The King, by Fox and Flash co-creator Harry Lambert; The Whip, by Doctor Mid-Nite creator Charles Reizenstein and Homer Flaming; and Hawkman, by Fox and Sheldon Moldoff; along with a “Minute Movie” feature by Ed Wheelan.

Sadly, Julius Schwartz never saw fit to revive three of these features during the Silver Age. Ghost Patrol, making just their second appearance here, featured French Foreign Legionnaires Fred, Pedro and Slim, who continued to battle Nazis even after being killed in action. The fought on from the afterlife until Flash Comics #65 (April 11, 1945), eventually showing up once more in the 2005 limited series Day of Vengeance, as well as a few issues of Shadowpact in 2006. The King was a master of disguise who otherwise fought crime in a cape and top hat. He made his debut in Flash Comics #3 (Jan. 15, 1940) and held on through #41 (March 10, 1943), also making five appearances in World’s Finest Comics and three in Comic Cavalcade. The Whip was DC’s first Hispanic hero, with a Zorro-like ship motif, hence the name. He fought crime from Flash Comics #1 (Nov. 10, 1939) through #55 (May 10, 1944) and has made sporadic modern appearances, with a son and a granddaughter having carried on his legacy.

Flash Comics, of course, ended with #104 (Dec. 8, 1948) in the waning years of the first heroic age, although the numbering was picked up with Barry Allen’s first title as The Flash #105, which sped its way to newsstands a decade later, on Dec. 23, 1958.

This issue will cost you anyway from $157 in Good condition, to $675 in Fine, and on up to $2,25o in Near Mint.

ACTION COMICS #49

ACTION COMICS #49

(on-sale Friday, April 17, 1942)

Early on, Superman did not face a lot of named villains, and even those who took on code names often eschewed costumed personas. One such baddie was The Puzzler, who makes his debut here, is an expert in parlor tricks and games of chance who forms a protection racket in Metropolis. Created by Jerry Siegel and John Sikela, with inker Ed Dobrotka, he’d make a trio of appearances before showing up in a few Batman comics of the the Silver Age as a kind of poor-man’s Riddler. The name has been re-used a couple of times for different characters in the modern era, always for villains.

This issue also features The Vigilante in “The Rainbow Man,” by Mort Meskin and Cliff Young; Three Aces (kind of like the Ghost Patrol, only not dead) in, “The Mystery of the Meandering Mansion,” by Louis Cazeneuve; The whip-wielding Mr. America in, “The Crime Machine,” by Ken Fitch and Bernard Bailey; Jungle explorer Congo Bill in “The Last Shipment,” by the incomparable Fred Ray, and Zatara the magician, a.k.a. Zatanna’s dad, in, “The Story of the Magical Mobsters,” by Fox and Joseph Sulman.

The range on this as a back issue purchase? Expect to pay between $310 (Good), $1,320 (Fine), and $4,400 (Near Mint).

ALL-AMERICAN COMICS #39

ALL-AMERICAN COMICS #39

(on-sale Friday, April 17, 1942)

This cover sports a rare acknowledgement, for DC at least, that there was a war going on, with the bullet in the lower right which reads, “Hop Harriggan says ‘Keep ’em flyin’.'”

Inside, it’s fairly standard stuff for the era. There’s the original Green Lantern by Finger and Irwin Hasen; Doctor Mid-Nite by Reizenstein and Aschmeier; aviator Harrigan by series creator Jon L. Blummer; Sargon the Sorcerer by Wentworth and Howard Purcell; military trio Red, White, and Blue, also by Wentworth and Purcell; and The Atom, by Bill O’Connor, Ben Flinton, and Leonard Sansone.

All-American would last until #102 (Aug, 20, 1948) when it would transmogrify into All-American Western, lasting in that form until #126 (on stands April 16, 1952).

If you have the will power to try and track down a copy of this comic, it will set you back something in the range of $190 (Good), $810 (Fine), and $2,700 (Near Mint).

MORE FUN COMICS #80

MORE FUN COMICS #80

(on-sale Wednesday, April 22, 1942)

You’ll remember in last week’s Time Bubble trip how we spent a lot of time talking about Green Arrow and the membership, or not, of his Silver Age incarnation in the Justice League of America. Here he is in his Golden Age glory

Having made his debut, along with Aquaman, in More Fun #73 (Sept. 25, 1941), GA took over the cover spot from Doctor Fate with #77 (Jan. 21, 1942), making this just his forth cover outing. But for the occasional Johnny Quick cover (on #86, 87, and 100), he’d hold the featured position though #101 (Nov. 22, 1944), when he’d give way to Dover and Clover as the title began the transition into becoming the humor mag, and in that form the fun would stop at #127 (Sept. 26, 1947), with the crime-fighting set shipped off to Adventure Comics as of #108 (Jan. 23, 1946).

This ish features GA & Speedy in “The Script Calls for Murder,” drawn by George Papp and probably written by Mort Weisinger; Doctor Fate in his only battle against, “The Octopus,” by Fox and Sherman; the fightin’ detectives of Radio Squad in “The Case of the Bearded Bandits,” by Young and an unknown writer; Aquaman versus Black Jack in “Champ of the Waves,” by Norris, also likely written by Weisinger; Johnny Quick, the “human projectile of mercy,” versus Nazi saboteurs (another rare bleed of current events into DC Comics) in “Code for Conspirators,” by Meskin and Young, also probably written by Weisinger; and The Spectre in “The Case of the Scholarly Spendthrift,” by Siegel, Pierce Rice, and Bernard Bailey

This issue goes for $2,600 in Near Mint condition, $780 in Fine, and $180 in Good.

ALL-STAR COMICS #11

ALL-STAR COMICS #11

(on-sale Friday, April 24, 1942)

Although socking foreign soldiers was common practice over at Marvel Comics, then known as Timely, and on covers of the Standard Comics line we know know as Nedor, it was a super-rare occurrence at DC. Here, in a story that must have been put into production shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, “The Justice Society Joins the War on Japan,” as each member joins the military in his civilian identity. The story is written by Fox with chapters drawn by Jack Burnley (Starman), Moldoff (Hawkman), Peter (Wonder Woman), Young (Sandman), Flinton (Atom), Sherman (Dr. Fate), and Aschmeier (Dr. Mid-Nite and Johnny Thunder).

This issue is notable for the team changing its name temporarily to the Justice Battalion, and because Wonder Woman joins the team. She has her magic lasso here, so this story much have been completed after the one in Sensation Comics that started this week’s column. Not a bad run, considering that following her debut in a preview in All-Star Comics #8 (Oct. 25, 1941) and six issues of Sensation, she gets full JSA membership in just her eighth appearance!

The JSA would, of course, fight on long after the end of WWII, with All-Star lasting until #57 (Dec. 13, 1950), when it would hop trends and become All-Star Western, starring the cowboy version of Johnny Thunder, lasting in that form all the way to #119 (April 4, 1961). The title would get revived as a JSA vehicle on Oct. 9, 1975, picking up at #58 as if the western issues had never been published. That title would die in the DC Implosion at #74, out on June 27, 1978.

This issue will run you $4,900 in Near Mint, $1,470 in Fine, and $345 in Good.

DETECTIVE COMICS #64

DETECTIVE COMICS #64

(on-sale Friday, April 24, 1942)

It was clear early on just who clicked with Bat-fans as the hero’s arch nemesis, as The Joker makes his second appearance this month. In “The Joker Walks the Last Mile,” by Finger, Kane, and Robinson, the clown prince turns himself in and is put to death in the electric chair. But he somehow survives and can’t be brought in by Batman because he’s already legally paid for his crimes!

This issue also features the debut of The Boy Commandos by Simon & Kirby, who displaced adventurer Cliff Crosby and private investigator in the ‘Tec line-up. Still on the roster however were super-heroes The Crimson Avenger, by John Lehti and Charles Paris, and Air Wave, by Murray Boltinoff, Harris Levy, and Paris, along with detective Slam Bradley, by Sherman, and spy Bart Regan, by Rice and Arthur Cazeneuve. We don’t know today who wrote the Slam and Bart stories. The Air Wave tale features the first appearance of his pet parrot Static. So, his sidekick was a parrot and his gimmick was that he traveled the city by roller skating across telephone wires! Why Grant Morrison has not done a revival I don’t know!

If you want a copy of this issue, expect to pay $7,500 in Near Mint, $2,250 in Fine, and $525 in Good.

ADVENTURE COMICS #75

ADVENTURE COMICS #75

(on-sale Wednesday, April 29, 1942)

Hey, look who’s on the cover, it’s the Mighty Thor! Looks a wee bit different that his later marvelous appearances though, doesn’t he? This is just the fourth outing for Simon & Kirby on Sandman, although despite popular belief, they were not the one’s to put him in traditional super-hero togs. That happened in #69 (Oct. 30, 1941), three issues before they came on the scene.

This issue also features S&K on their version of Manhunter. Plus there’s Starman by Fox and Burnley; adventurer Steve Conrad by Lehti; The Shining Knight by Henry Perkins and Cazeneuve; and Hourman by Bailey.

This is a $3,000 book in Near Mint, although you can probably manage to score a Fine copy for $900, or a Good for $210.

And finally, just for giggles, we might as well mention the April 1942 adventures of a few characters from other companies who would eventually become part of the DC family:

On sale April 3, 1942:

CAPTAIN MARVEL ADVENTURES #10 (Fawcett Publications) — Has five stories all starring the Big Red Cheese himself, the original Captain Marvel — that’s SHAZAM to you and me, pal!

HIT COMICS #22 (Quality Comics) — Has Stormy Foster on the cover, with the Red Bee among the characters inside.

MASTER COMICS #26 (Fawcett Publications) — Features Captain Marvel Jr. with additional tales starring Bulletman, Minute-Man, El Carim, Buck Jones, and the Companions Three.

UNCLE SAME QUARTERLY #3 (Quality Comics) — Five stories featuring the fighting visage of American pride.

On sale April 8, 1942:

NATIONAL COMICS #10 (Quality Comics) — Stars Uncle Sam on the cover, while characters include include Quicksilver, the speedster known to modern Flash fans as Max Mercury.

On sale April 10, 1942:

MILITARY COMICS #10 (Quality Comics) — Is a vehicle for Blackhawk among its many features.

On sale April 17, 1942:

WHIZ COMICS #30 (Fawcett Publications) — Features include Captain Marvel, Golden Arrow, Spy Smasher, Lance O’Casey, Dr. Voodoo, and Ibis the Invincible.

WOW COMICS #6 (Fawcett Publications) — Mary Marvel has yet to make her debut, so we’re stuck with Mr. Scarlet, Commando Yank, Phantom Eagle, and Spooks.

On sale April 22, 1942:

SPY SMASHER #5 (Fawcett Publications) — Sees the scourge of saboteurs halfway through the 11-issue run of his solo title.

On sale April 24, 1942:

FEATURE COMICS #30 (Quality Comics) — Has Doll Man among its features.

And that’s it for this Time Bubble trip. Come back next Friday when we’ll skip ahead to the third week of April in 1982 — 35 years ago — as the New Teen Titans face off for the first time against Brother Blood, a character now known to millions for his run as the big-bad on Season 1 of The CW’s Arrow.

Until then, remember — “Hey, Kids! COMICS!!”