American professor of literature, Joseph Campbell, wrote of mythology “one of our problems today is that we are not well acquainted with the literature of the spirit. We are interested in the news of the day and the problems of the hour.” Campbell stated in the simplest terms the importance of fiction and story to the human experience. “If a being from another world were to ask you, ‘How can I learn what it’s like to be human?’ a good answer would be ‘Study mythology’.” For many, mythology is the ancient stories of old gods and tragic heroes but mythology is not a set group of stories from a determined point in time. Mythology is human communication through fiction. It is how we reflect ourselves- emotions, flaws, dreams, and fears- in a way that will translate to those with whom we seem to share little common ground. When the American experiment started, the culture was a fractured image of cohabitating histories, but by the time comic books became a distributed medium, it was a country ready to contribute to humanity’s story as a unit. Comic books and superhero stories became the vessel for that contribution.

If you grew up reading comics or aspiring to create them, it’s unlikely that the passion seemed to hold that kind of weight. When you’re an adult, you’re told comic books and superheroes are kids stuff. When you’re a kid, you’re told it’s nerdy, unattractive, or strange. On a personal level, my classmates informed me it was weird to be interested in comics at eleven years old. Now at twenty-four, I’ve come to believe the bias is more about invalidating a method of interaction with the world than it is about discerning maturity. I bring Joseph Campbell up as an academic backing to the position I have- that comic books and superheroes are important and represent the evolution of a kind of story that always has been valuable to the human experience. There is no flaw in liking them, and no true otherness in being enthusiastic about it.

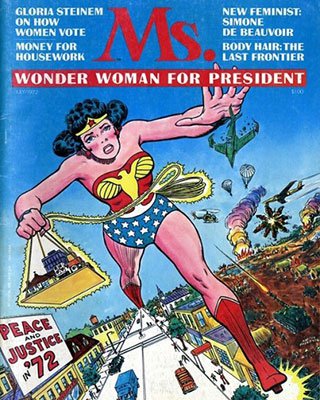

Superhero stories are woefully underestimated as cultural mirrors. The idea that they are one-dimensional pop culture images is a misinterpretation. From her creation, Wonder Woman opened a discourse about female strength and empowerment. Diana Prince became a symbol of the complex role women took on in World War II and has transformed in every decade since to reflect an idea of what womanhood means. It is, of course, one idea that can be discussed and disagreed upon. Wonder Woman gives individuals access to that discussion on a level they may not have otherwise had. Likewise, Batman and Superman help us explore reactions to crime as both an intense mental exercise and a moral divide that can cross into grey areas- no matter how noble the heroes intentions may be. We look for ourselves in these images and wade through questions of how our moral compass shifts. Superhero stories are a core method of self-exploration and exactly the kind of spiritual literature Campbell described.

To assume comics and superhero stories are unimportant is to discredit a type of uniquely American mythology, one forged in the hard work of individuals with different backgrounds and bonded by the common goal of making an imprint in the fabric of their communities. Comic creators tell their own stories in a way that allows readers to connect. We watch the impossible play out while exploring honest emotion and discussing real values. When superheroes leap from the page to the screen, they make these discussions even more accessible. Comic fans and creators don’t always see eye to eye, in fact, sometimes it feels we rarely do. These conflicts stem from a community that cares about individual values and holds them in high regard. I would argue that a world which values self-expression, even in conflict, is better than one that does not look to communicate those ideas at all or demands communication through rigid, unimaginative methods.

These stories should not be mistaken to have suddenly shifted audiences in recent years. Comic writers of the golden age considered the possibility of using the medium to tell more complex stories. Over time, that dream has become a proud reality. Appreciation for comics in an older demographic is not sudden or recent. It has evolved from the influence of dedicated fans and passionate creators. These creators, men like Stan Lee, Jerry Siegel, Joe Shuster, and Bill Finger used whatever talents they had, no matter how insignificant others may have considered them, to engage in the dialog of a changing society and share in the experience of human connection. To see a method of art or self-expression as invalid is to encourage apathy and wasted talent. On the most basic level, dismissing their accomplishments is cruel. Doing so strips away the validity of an entire community’s method of connection and dismisses lifetimes of passionate work. The people creating comics are rarely looking for their chance at fame, fortune, and blockbuster movies. More often than not, it is about toiling away to tell a story and send a message that matters to the individual.

Setting aside superhero stories as a focus, it should be noted that comic books are not a genre but a medium. For anyone unfamiliar with the concept, a genre is a specific type of a given medium. Superheroes are a small genre in the larger comics medium in the way that watercolor is only one way to paint. Even if you dislike watercolor, it would be ridiculous to say that all paintings are bad based on that preference. Similarly, hating Shakespeare is not an indication of hating all theater. That idea would neglect the dazzle of Broadway musicals, the drama of Tennessee William’s works, and the raw darkness of Samuel Beckett’s plays. It is unfortunate to see how narrowly comics are viewed as a form of art. Comics are both a literary and artistic medium combining written word with visual imagery for the sole purpose of telling a story. It offers limitless possibilities to those creative enough to think on both planes and promotes collaborative efforts between artists with specialized talents. Nowhere else can pictures and words coexist in such tandem and allow readers to engage with the creation at their fingertips. In my opinion, there is nothing childish about wanting to appreciate art and enjoy a good story at the same time. I see nothing immoral about valuing that.

Comic books and the superhero stories they champion are a unique transformation of the type of stories humans have held close to their hearts for centuries. When separating the two, there is still much to appreciate about comics that do not focus on heroes and much to appreciate about superhero stories told on screen. Not everyone has to get it, not everyone has to appreciate it personally, but completely disregarding a medium of art and method of human connection does not strike me as okay. Human beings have the right to contribute to the world using their natural talents. It would be a shame to deny that right just as it would be a shame to invalidate our modern world’s contribution to centuries of mythology.