Review: WONDER TWINS #6

[Editor’s Note: This review may contain spoilers]

Writer: Mark Russell

Artist: Stephen Byrne

Letters: Dave Sharpe

Reviewed By: Ari Bard

Summary

Injustice. Millions of people experience it every day. It’s all too easy to ignore until it happens to us. For some, it’s unavoidable, and Mark Russell, Stephen Byrne, and Dave Sharpe examine the injustice that happens to ordinary people through the scale and dramatic flare of a superhero story.

Positives

“‘How much human genius rots outside the wall simply because the gates of opportunity were locked to them?'”

We talk about superheroes and their good deeds as often as we can these days. With all of the movies and TV shows coming, we can’t seem to get enough of watching superheros punch out the bad guys for the greater good. But let’s talk about those bad guys for a second. Some of them, the big supervillains we always see on screen for example, appear to have a choice. They are malicious and commit acts of evil because they derive satisfaction from doing so, but what about the smaller villains or the lowly henchman? They’re often labeled as freaks or denied opportunity and had to turn to this life in order to survive. Some of them may not have wanted a life where they have to do the wrong thing, a life of always living in fear, or a life in an out of a prison cell, but the gates of opportunity were locked to them.

Maybe that’s darkening the mood, or maybe you’ve never thought about it that way, and that makes sense. We rarely focus on the “lesser” villains and rarely try to sympathize with them because they’re never considered as interesting. In the exaggerated world of good an evil, love and violence, hope and fear, and all of the other dualities that comics inundate use with, the henchmen and “C-level” villains always seem to come across as bad, annoying, disrespectful, inconvenient, or surprising. You never expect them, but they rarely dramatically change your views or cause trouble for your favorite superhero saving the day. To be quite frank, many people see them as uninspiring and silly. They don’t matter. Until they do. It’s why a book like Kurt Busiek’s Astro City has always been so fascinating. It took a minor villain or henchman and explained that they don’t always have a choice. Superman is powerful, and his powers are useful. No matter how large or small the situation, he can always lend a hand in some way. What about Praying Mantis? How many situations would you call him for help? Likely none. How many local business would hire someone with his appearance? Likely none. His set of powers, mutation, or whatever you want to call it limits his opportunities because of society’s biases. He likely turned to crime because it was the only way he could get ahead and survive in this world.

That’s not to say superheros are bad. They inspire and represent the best parts of all of us. But wouldn’t you agree that some of humanity’s limitations are what creates a bigger need for superheros in the first place? Our prejudices, hate, and violence force groups of people into the shadows and into a life they may not have wanted. The superhero reminds us of how to be a solution and how to use generosity, love, and hope to help and heal others. When we see a supervillain, however, it reminds us of how we can be part of the problem. Is this really something they are choosing to do for enjoyment? What controllable, societal circumstances drove them into this life? It’s something we rarely think about, and it’s hard to wrap our heads around, but it’s something we should examine more often.

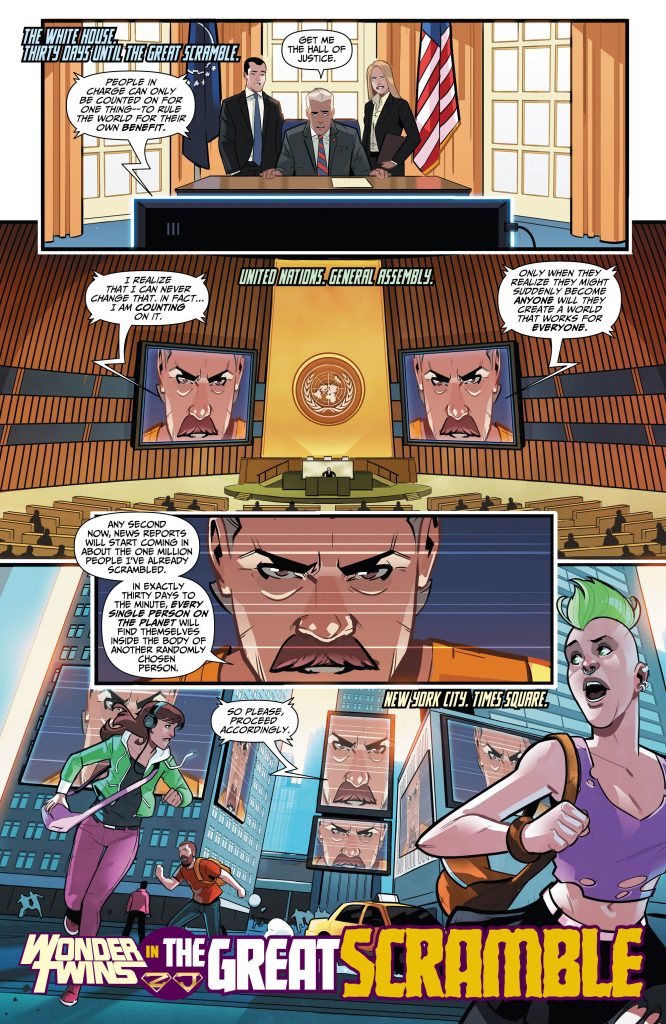

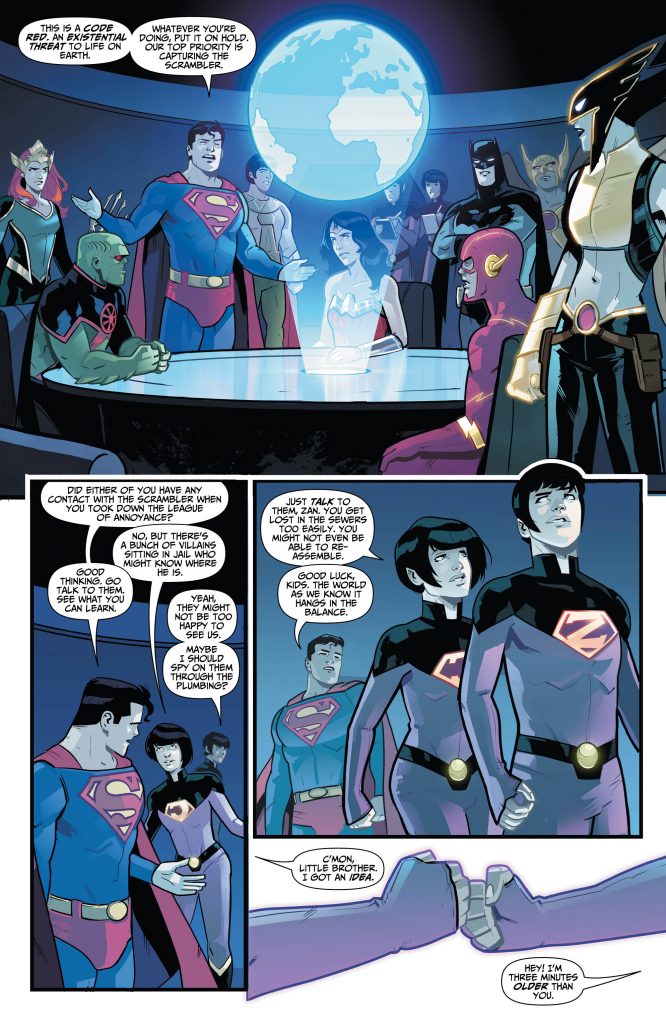

Perhaps it’s something most of us could never truly understand because most of us will never experience it. Some people get upset when they see an issue of their favorite comic focusing on a enemy their favorite hero could easily defeat? Why should we care about them? They can’t pose a threat. Look at Tom King’s Batman: War of Jokes and Riddles, a comic arc revolving around Kite Man of all people. There are a lot of people who strongly disliked this arc, and Kite Man was largely the reason. His story was tragic and his loss was heartbreaking, but why should we care? He can’t really do anything. Wonder Twins devotes its pages to a similar subset of people. It’s where the interesting gray areas lie. It’s about people driven to “villainy” by circumstances beyond their control. It’s about people more similar to each of us than they are different trying to demonstrate the need for equal opportunity through the only methods they think will get the message across. Up until now, Wonder Twins has been largely comedic in nature. In Wonder Twins #6, however, the comedy takes a back seat to the more serious issues of injustice as the arc reaches its conclusion. There’s still some great one-liners, funny panels, and hilarious dialogue sprinkled throughout, but it’s less to poke fun and garner a laugh than it is to make you think. More than anything, Wonder Twins #6 invokes feelings of anger, frustration, and sadness but also inspiration. The issue hopes to inspire its readers to stand up for what’s right and be the change they like to read about in the pages of comic books. Mark Russell, Stephen Byrne, and Dave Sharpe wrap up the first arc with Wonder Twins #6. For awhile, this was it, and the story ended here. We know now that the series was extended for six more issues, but for awhile, this was the end. Does the day really feel like it was saved? It shouldn’t because it wasn’t. Ignoring the fact that The Scramble is still very much a threat, in the end, Polly didn’t get her father back, she’s going to prison, the Scrambler is satisfied knowing that he was right, and Jayna lost her first friend on Earth. It’s a hollow victory at best.

If the creative team had to pick a theme for this arc and final issue, it’d likely be change. It’s a concept simultaneously missing and ubiquitous throughout superhero fiction. The phrase, “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” could not apply more in this context. We always see superheroes looking to inspire change and help people be better. They have hopeful catchphrase and do inspiring deeds, but does anything really changed? Have they really solved the problems we’re facing today? Climate change, war, poverty, mass incarceration, and inequality are some of the issues that haven’t been fixed my heroes. Superheroes themselves have changed frequently over the years with new heroes and costumes popping up left and right, but the betterment of humanity appears to be the case even the world’s greatest detective can’t seem to solve.

Let’s look at how The Scrambler views change. Last issue we saw him use magic as a metaphor for how society views change. The first step is The Pledge promising the change. We see a lot of those don’t we? In comics we see bad guys promise to be good and heroes promise to change for their loved ones while striving for better balance, safety, or happiness. In real life we see individuals and institutions promise change all the time. Politicians promise to make change happen every day, when people protest organizations for better rights, equal rights or against injustices, those organizations promise to change too, but how many times does it really happen? Next is The Turn, where the change actually happens. It’s not very often that we get this far, but every now and then, we’re shows some seemingly tangible results. People often react to these changes with overwhelming joy or violent anger. Those that are joyous clap usually because they believe it’s a trick. When villains are defeated, we act all happy, but if they ever returned and we never saw them on screen or in a comic again, we’d be pretty upset. Whenever seemingly permanent change does come, there are always cries of outrage. How dare someone threaten the status quo! Change has grown to imply something worse and negative even before people give it a chance. Change implies discomfort, and we hate that. In the end, all we want is The Prestige: the notion that permanent change could happen if we wanted it to, but that everything will turn back to the way it was. We love our normalcy, and we love our comfort.

This is what Mark Russell and The Scrambler try to present in Wonder Twins #6. Mark Russell is the kind of writer who will always find ways to speak his mind, and Wonder Twins is no different. People may and will criticize, but these messages need to be out there. Alongside Stephen Byrne’s art, which serves to remind you that this is fiction and should be lighthearted, even if it has something to say, and Dave Sharpe’s lettering, Russell uses The Scrambler to show the power of people who actually want to change the world.

Polly Math experiences very similar feelings, and understandably so. Her mother was killed in the crossfire of a battle between billionaires she had no part in. He father was seemingly killed by a bigoted old woman with a cell phone and received no justice for it. At this point, Polly just wants to live her life as her own ans not as some puppet for a wealthy individual. Jayna doesn’t even argue against Polly’s reasoning or motivations, only her methods. But Polly’s tired of just being complacently good. Her mother and father were good people who made a few mistakes along the way and were killed for it. What’s the use of being good if that’s where you’re going to end up? Are Polly’s beliefs so horrible? Even if you don’t share them, can you see where she’s coming from? The world isn’t working, and Polly refuses to just be another person swept up in the debris. Instead, she decided to use her genius to change the world, and now she’s been punished for that too.

Zan and Jayna feel a palpable and understandable sense of helplessness in this issue as well. When Jayna confronts her best friend, she does something that few heroes seem to do: she listens. Instead of resorting to punching and violence right away, she sits down as a friend, and after listening, Jayna doesn’t seem to have anything to say. Polly’s grievances are spot on. Jayna may not agree with the methods, but she also has no answer to the question, “If your good doesn’t matter, what does it matter if you’re good?” other than reminding Polly that people may die and reminding her that it’s not her job to fix the world. Polly get’s the last word in, however, when she states, “No. it’s yours,” which begs the ultimate question: How much good are the superheros of this world really doing? When Jayna realizes that the threat of The Scramble was enough to inspire change on its own, her first impulse is to saver her best friend. Isn’t that more heroic than anything the Justice League could muster in this issue? Unfortunately she’s too late and arrives at Polly’s house to find the League already ripping it apart. Did they need to rip the roof off in order to catch a teenage girl and a villain whose powers can only happen by touch? Absolutely not, but they did it anyways. Maybe it made a great photo.

After all this unfolds, it’s easy to blame Zan. He is the reason Polly and The Scrambler got caught, but are his action so wrong? Sure he can be a bit dense, like when his first thought after the threat of The Scramble is the threat to his varsity hockey letter, but he always has the best intentions. Just like Jayna, Zan goes to the prison to find information and uses his words first instead of physical intimidation. He approaches solving the problem the right way. When Superman encourages Zan and Jayna to wait The Scramble out off planet, Zan politely refuses because he’s accepted his new home, and in the end, he finds the villains and saves the day. It’s easy to get mad because, after all, it doesn’t really feel like Zan saved anything, and he knows that. He’s smart enough to realize how this looks and how broken this planet is, but he’s loyal to the end, and to Zan being loyal to Superman meant doing the textbook right thing, even if it didn’t feel right in his heart. Is that so wrong? It certainly doesn’t feel like it.

So Wonder Twins #6 ends up asking the question: what is the right answer? Like many other situations in the our world today, it doesn’t feel like there is one. Everyone in the issue is doing their best to inspire change in different ways, and ultimately, they all just cancel each other out. This is a book dealing with problems that can’t be fixed with superpowers. It forces us to look at and become superheros in a different way. Where do we have the responsibility to make changes in our society that superheroes can’t? It’s a question this creative team asks, and one unlikely to receive many answers.

Ultimately, Wonder Twins #6 is a tragic conclusion. Not only does it feel like nothing was fixed, but it also feels like no one really did anything wrong? What crimes with they even be charged with? There was no intent to kill anyone, and there was no guarantee that anyone would die, so attempted murder is out of the question. Attempted mass identity fraud? Reckless endangerment? Those don’t exactly fit right either. There really doesn’t seem to be anything criminal about switching bodies, even if it feels wrong, but The Scrambler and Polly are going to jail anyways because that’s how our society works. This is a book that wants you to accept the reality that there is no right answer, and take the necessary steps forward anyways. It wants you to take action, even if the plan isn’t perfect. It wants you to recognize the oppression and injustice occurring to people all over the U.S. and the world, especially to people of color, and it wants you to take action now, because good intentions never solved anything. If you still have doubts, just ask yourself, what ever happened to the one million people that got scrambled in the first place?

Verdict

With Wonder Twins #6, Mark Russell, Stephen Byrne, and Dave Sharpe deliver a poignant and powerful conclusion to one of the of the most honest, topical, and necessary comics on the shelves.