Let’s start with a celebration of impossible things. In the early 1990s, the Master of Dreams found his place in the public’s imagination and an interstellar poet faced human madness head-on. In the 2000s, fairy tales came to life in the grit of New York, and we all found a little sympathy for the devil. Comic book fans have a lot to thank DC’s Vertigo imprint for. Sandman, Swamp Thing, Shade the Changing Man, Fables, Preacher, and dozens of other beloved series hit their stride under the Vertigo label. When DC announced that Vertigo would be taking its final bow last year, generations of loyal readers felt the wave of heartache.

Launched by DC editor Karen Berger in 1993, Vertigo took on titles that challenged readers; in some cases providing existing books with support and creative breathing room, and in others, nurturing stories that seemed too crazy or taboo for mainstream publication. The result of Vertigo’s creative risk-taking is a legacy of brilliant storytelling, complex characters, and adoring fans. The imprint has made a lasting impact on the comic book industry by showing publishers that non-traditional comic narratives can survive in a competitive market. Better yet, Vertigo drew new readers to the stands in droves, proving to the world that DC had more to offer than spandex-clad superhero stories. Readers took the message to heart. Many found the inspiration to craft stories of their own and bring fresh ideas and concepts to the larger comic book community.

We are no different here at DC Comics News. From editorial staff to news writers, podcast panelists to reviewers, Vertigo has impacted our creative roots and helped shape us into the comic fans we are today. With respect, gratitude, and fond nostalgia, we would like to share just a small piece of how much Vertigo has meant to the members of our team.

Our Panel of DCN Contributors:

Josh Raynor: Editor-in-Chief at DC Comics News.

Steve J. Ray: Editor-in-Chief at DKN (Dark Knight News) and writer, reviewer, interviewer, podcaster/multimedia journalist for DCN and DKN. Also known as Geekipedia.

Seth Singleton: News writer, review writer, host of The Spinner Rack podcast, co-host of DC Comics News podcast.

Brad Filicky: Contributing writer and podcast talker for DCN.

Derek McNeil: Regular DCN review writer for a number of titles, including The Flash, Superman, Batman, and Justice League, as well as other DC properties.

Matthew Lloyd: News editor, opinion writer, DCN review writer.

Kelly Gaines: Opinion/editorial writer, co-host of the DC Comics News podcast, writer of this article.

What is your favorite Vertigo book?

Josh: Hmmm, let me think. I’d have to say Scott Snyder’s American Vampire. I love vampire lore and Snyder really did something special here.

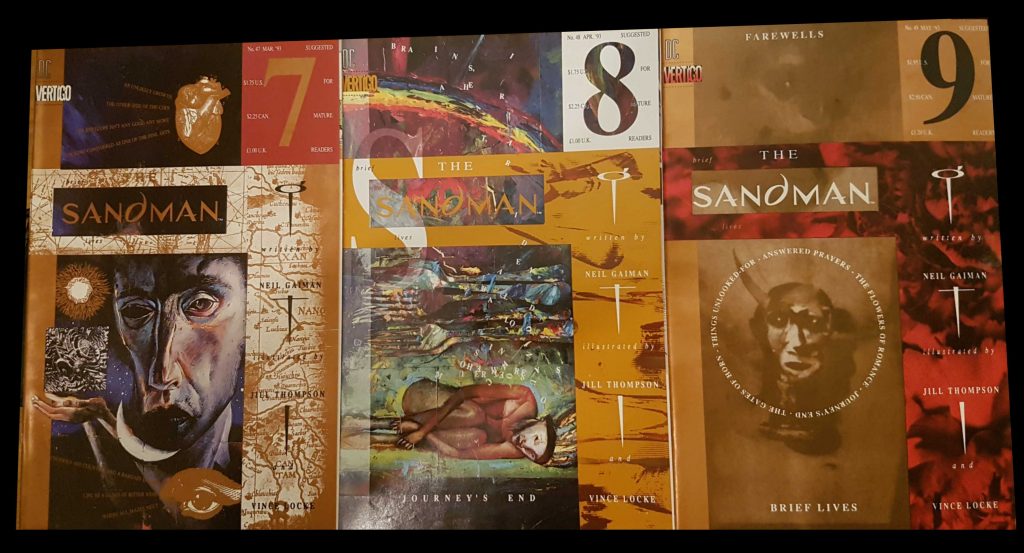

Steve: That’s HARD! If I had to pick just one, it would probably have to be Neil Gaiman’s Sandman. The tireless research by the author, the revolving stable of incredibly different artists, then the situations, worlds, characters, emotions and imagination behind all those stories elevated them, making them far more than just comic books.

Seth: The current run of Hellblazer and Lucifer titles. Dan Watters is a G.

Brad: Sandman and Preacher.

Derek: I honestly wish I could say that it was Animal Man, but honestly Animal Man was much better before it was imported into the Vertigo line. Not that I disliked what it became under Vertigo, but it didn’t come close to what it had been pre-Vertigo – especially the initial Grant Morrison run. That is one of the most brilliant storylines to grace a comic book, which unfortunately no Animal Man title has quite been able to match. My actual favorite would be Sandman. It was an epic storyline even before it was incorporated into Vertigo, but that quality kept up, even improved under the Vertigo banner. Partially, this was because Neil Gaiman continued writing the story for its entire run. I also think that Vertigo’s adult-oriented mandate allowed Gaiman a lot more creative freedom. Also, Sandman kept its ties to the DCU, but was kept at an arm’s length from DC’s core line, so there was more freedom there.

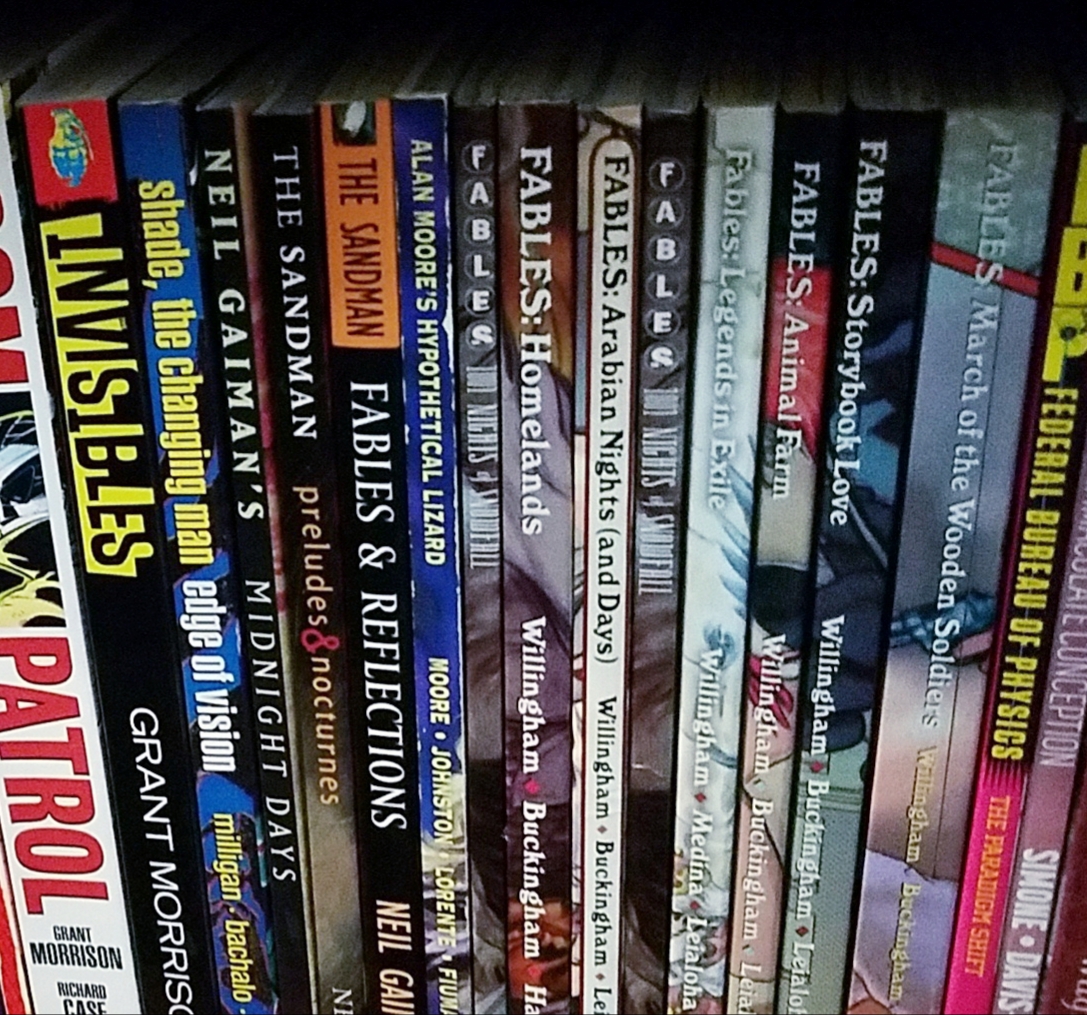

Matt: Fables.

Kelly: I have Fables to thank for taking me from an occasional comic reader to a fanatical “comics are one of my bills” kind of reader. My childhood was centered around fairy tales. I knew the Grimm’s stories by heart before I could even read them myself. Watching elements of stories that shaped my childhood play out with relatable human emotion and raw imperfection was cathartic. Once I got hooked on Fables, my idea of both comic books, and storytelling as a whole, started to morph into something more personal. It started to become a medium I wanted to be a part of.

Was there an author that spoke to you the most? If so, what drew you in about their writing?

Josh: Definitely Neil Gaiman. What he was able to create with the Sandman series was something beyond description. It opened up a whole new world for me outside of the typical superhero fare I had been used to reading.

Steve: Again, Gaiman. He brought long-forgotten characters from DC’s back catalog to the present and fundamentally changed them, while still keeping them true to their roots. He kind of changed them, but without changing them at all… if that even makes any sense. He also nurtured and developed many ideas posed by Alan Moore – whose Swamp Thing was one of the main catalysts for the Vertigo imprint being created in the first place – and ran with them in a way that no-one else has been able to, except possibly James Tynion IV during his run on Justice League Dark. What drew me in was the imagination and the lack of constraints and censorship. These books didn’t contain gratuitous violence or sexuality but were adult psychologically, in the real grown-up sense. This wasn’t just an outlet for adolescent titillation or gore. It was far deeper and richer.

Seth: Neil Gaiman. He made me think about Lucifer in a new light. He made me laugh at the beautiful details that make a story sing with original voices that were beautiful, jarring, and unapologetic.

Brad: Garth Ennis and Neil Gaiman, but I guess my answer to the first question kind of gave that away. What drew me in were the characters and the dialog – the overall themes and plot – I couldn’t get enough.

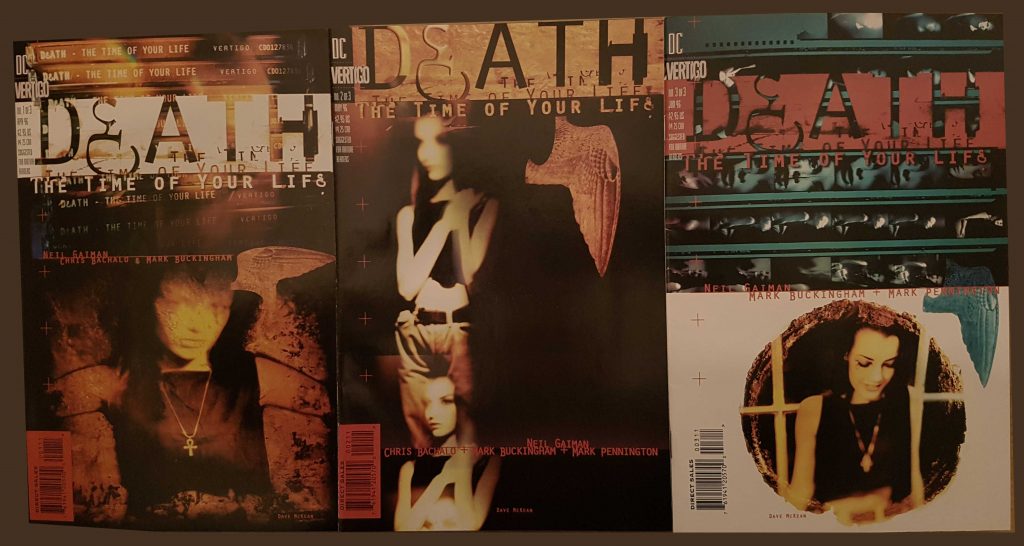

Derek: Well, again I would have to go to Neil Gaiman. Sandman is what first drew me to him, but he also created a number of other Vertigo properties. There was Death: The High Cost Of Living, The original Books Of Magic mini, and he did Vertigo’s only crossover event, The Children’s Crusade. And a number of his characters went on to their own minis or ongoing series, like the Dead Boy Detectives, The Dreaming, and Lucifer. And as we know, Gaiman has returned to curate a revival of some of these titles under the Sandman Universe banner. [As far as what drew me in] I was sort of grandfathered in. I was reading pretty much all of the DCU titles. When Vertigo launched, the core titles were DCU titles that got incorporated into the Vertigo line: Doom Patrol, Hellblazer, Swamp Thing, Animal Man, Sandman. These were all firmly set in the DCU, as was the original Books of Magic mini. And further DC mainstream characters were featured in Vertigo projects, like the Phantom Stranger, Black Orchid, and especially Sandman Mystery Theatre, featuring the Golden Age Sandman. So, ultimately, it was the ties to the main DCU that drew me in.

Matt: Bill Willingham, obviously, but Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore get special mentions as two of the first Vertigo writers. What drew me in were the genres besides ‘the superhero’. Vertigo opened up an opportunity to break out of the standard Superhero genre at DC comics. It also allowed for creator-owned concepts.

Kelly: Neil Gaiman. I’ve been working my way through Sandman on and off for several years and Gaiman’s ability to build characters around classic lore brings me back each time. His storytelling radiates natural confidence. Reading Gaiman is like getting in the car with an expert driver on a road you know they’ve driven a thousand times. You trust his methods and you trust him to take you exactly where you need to be. The fact that it’s a hell of a ride is just a bonus. The characters drew me in. Vertigo characters don’t shy away from showing the ugliest parts of human nature. That sort of unashamed vulnerability is beautiful to me. In Vertigo books, a man can be an element, a god can be a friend, and a devil can be truly sympathetic. Comics have always been good at pushing those envelopes but Vertigo felt like it was doing so in a more brash way.

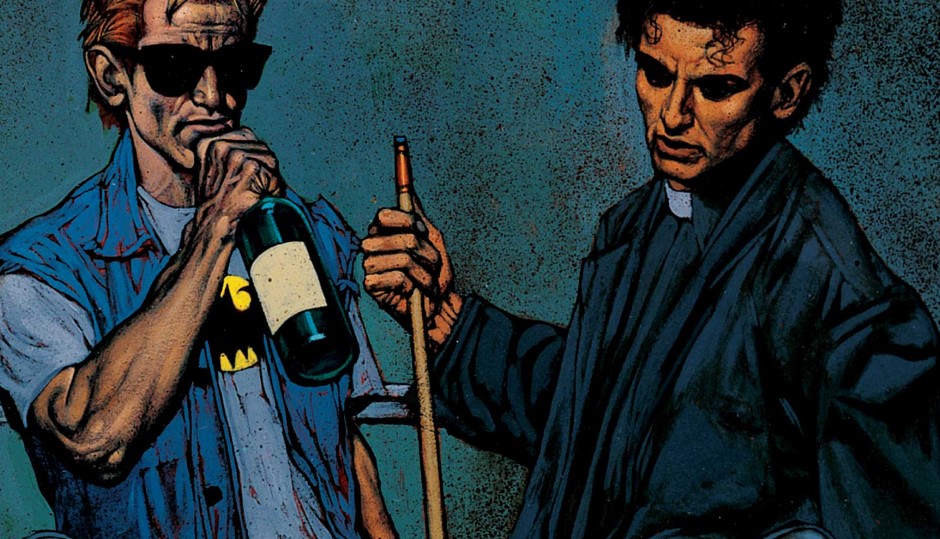

The limited “Death” (1996) series from Neil Gaiman. The series explored one of the Sandman universe’s most popular characters, Death. This photo was taken from Steve’s extensive collection.

When did you first read something from Vertigo and what was it?

Josh: I discovered Vertigo late in my comic book fandom. It was my sophomore year of college in 2003. My English professor assigned us The Sandman Vol. 1: Preludes and Nocturnes and I was floored after reading it; so much so that I had to seek out the rest.

Steve: I count Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, Watchmen, and V For Vendetta as Vertigo, even though they came before. Alan’s versions of the Green, the afterlife, the way he handled classic characters like Deadman, Etrigan, the Spectre, and the Phantom Stranger, plus his own original creation John Constantine, were the foundations of Vertigo. They were the seeds from which Hellblazer, Fables, Sandman, Death, and so many others grew. I was there at the beginning, in 1993, and can honestly say that, as a 23-year-old man about to get married and on the verge of quitting comics, Vertigo drew me back in, and I haven’t looked back since.

Seth: I first found Vertigo in 8th grade. I wasn’t allowed to own them but I could sneak peeks with my friend who collected Sandman and The Books of Magic.

Brad: It was Sandman in the mid-1990s.

Derek: I suppose it would have technically been Vertigo Preview #1, released December 1992. It contained excerpts coming up from the first issues that would bear the Vertigo banner, plus a short original Sandman story. The actual first official Vertigo title, however, was Gaiman’s Death: The High Cost Of Living. Although I don’t specifically remember it being the first, it was the first to be released, and I got it when it came out, so it must have been the first I read.

Matt: It was Animal Man and Doom Patrol when they switched over to the Vertigo imprint (January 1993). I was reading those titles and I kept on reading the when they switched. I also remember enjoying Sandman Mystery Theater (1993-1999) immensely.

Kelly: The first Vertigo book I read was Fables Vol. 1. I was in high school at the time, so roughly around 2010 or 2011. Fables had already been running for a while at the time, so I was basically playing catch up, which was fine with me because it meant that when I got to the end of a book the next one was already available.

Original issues from Neil Gaiman’s “Sandman” courtesy of Steve.

Did anything change for you as a comic reader afterward?

Josh: Oh, absolutely! I didn’t think I could find stories like these in comics, stories with deeper meanings and thought-provoking commentary on the world we live in.

Steve: Everything. Our colleague Brad and I frequently say that titles like Sandman, Death, and Fables are literature. This isn’t hyperbole, it’s fact. These comics changed the way people looked at the medium; not just fans, but the world at large. It proved that comics could provide stories as creatively and eloquently as prose novels or films could.

Seth: I wanted my villains to be more human. I wanted my heroes to be more flawed. I wanted to know what song they listened to when they were drunk and uninhibited. I wanted to walk the planes between worlds and sit down for coffee with Lucifer and the Dream.

Brad: For me, it was when comics became literature – I’ve had off and on periods of collecting comics and the Vertigo titles were the impetus of me getting back in comics around 1996.

Derek: There wasn’t a sudden change really, most of the books that became Vertigo books had already shifted to a more adult sensibility. The books transplanted from the DCU had already been labeled as “Suggested for mature readers” for a few years. It did have a practical effect on my comic collecting though. I was buying a lot of titles, and limited funds meant I had to make some decisions about what to buy. It was at that point I fully committed to DC and dropped Marvel from my buying. Vertigo also started bringing out more and more stuff that wasn’t connected to the DCU at all – mostly creator-owned type stuff. That gave me more stuff I could cut down on. I wish I could have bought more of that stuff now, but my decision then was to cut my buying down to the main DCU stuff, plus whatever Vertigo was still at least vaguely connected.

Matt: For me, the Vertigo line echoed a lot of the independent comic companies that populated the landscape from the early to mid-’80’s- First, Pacific, Eclipse. It provided the same opportunities for creator-owned work and other genres without the constraints of the Comic Book Code. Back then, the code could be worked around a bit, but there were clearly things that were off-limits. Consequently, I’ve been drawn to lots of different genre books even if my mainstay is the Superhero.

Kelly: I started reading more comics after Fables. As I mentioned earlier, this was the series that made me a regular at the comic shop. I don’t think I was fully aware of the complexity of comics before Fables. I knew there were superhero stories, and I loved them, but Fables brought me to the edge of a new frontier. After that, I needed to keep reading and experiencing every comic I could get my hands on. I came out of Fables and sort of crash-landed right into the New 52 era at DC. I essentially began trying to pick up everything because I realized how much more there was to comics. That’s also when I started picking up more Image books.

A portion of Kelly’s comic book collection featuring “Fables”

Describe some of the creative lessons you learned from Vertigo.

Josh: I think the biggest lesson I’ve taken from Vertigo is that you don’t have to settle for what’s already there. It’s alright to be different, to push the limits, because sometimes you get a masterpiece.

Steve: As I’ve mentioned, [Vertigo books] weren’t gratuitous gore-fests. They taught me restraint, and how sometimes what you don’t see is scarier than shoving things on your face. A transformation witnessed from the shadows, or out of the corner of your eye… or sometimes not even seen at all, but experienced through the sound effects, described far more vividly what was actually going on in places you couldn’t (or didn’t want to) see. Also, pacing, expressions, emotion, and the long game. Sometimes a character or object mentioned in a line, or seen in a panel would become vastly important later in the series’ run. This made you scramble through back issues to read them again just to find out where you’d heard that name, or seen that object.

Seth: I know so little and I can learn so much. In the case of Lucifer, it is humbling to watch the insidious tenacity of horror and suspense unfold with the patient knowing and certitude that Dan Watters masterfully portrays. It’s brilliantly layered and designed to close one loop and leave so many more untied and there for the explorer to wander and discover.

Brad: If anything, Vertigo titles showed that there was nothing off-limits in the comics medium. Comics have always been imaginative, but these books had the true depth missing in most cape books.

Derek: Well, not Vertigo specifically, but I think it was more the wider movement towards adult-oriented comics. Comics were starting to become more complex with deeper, more nuanced stories. Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns was probably the first book to break the perception that comics were simplistic stories for kids and could be a valid type of artistic expression. But comics had already been moving that direction. Plus, I also saw that comics didn’t have to be about superheroes to be good. Vertigo opened me up to horror, science fiction, and other genres that I hadn’t really paid attention to. But this didn’t mean that superhero books couldn’t be good either, and Vertigo did demonstrate that somewhat, but the superhero stuff mostly ended up relegated to the main DC line.

Matt: Mystery and the plot twist. The surprise. Mysteries are a great way of getting a reader hooked early on.

Kelly: As a writer, I would say Vertigo taught me a lot about perspective. We tend to read stories at face value and not necessarily think about what would change if we read it all again from another character’s point of view or in the context of a different time period. Through Vertigo, I learned that you can look at something as set in stone as a bible story and find new ways of exploring ideas and personalities. In short, Vertigo pointed me at Pandora’s box and made a good case for opening it.

As you developed as both an individual and a writer, what kind of stories helped you along most? What did you find yourself drawn to?

Josh: Horror was what grabbed my attention the most. But it was more than just about horror, it was about compelling stories, and Vertigo had those in spades.

Steve: The stories that were disguised as fantasy or horror, but were actually tales about life, love and surviving in a world that didn’t make it easy to. I learned more about racism, sexism, intolerance, and bigotry (and how to fight them) from comics than I ever did from friends or family. Some of those comics taught me how to be a better human being; lessons I hold close to my heart to this day.

Seth: Stories about the wonders that exist outside the mundane world continue to appeal to my desire for more than the daily doldrums. But I am always pleased that they offer the same challenges that we face in the real world, even if they can illuminate the solutions in a more enjoyable fashion or environment. I felt that stories about characters who can be great in one moment and then tragically inept at something else (for some reason Constantine comes to mind) were engaging and comforting, no matter the context or the concept.

Brad: Preacher and Sandman. I can’t stress the importance to my life that those stories exemplified.

Derek: Well, as DC shifted their focus from a kid audience to adults, I happened to fall at about the right age where I was in the core audience for the entire process. I got into comics in the 70s. The stories were already gaining some complexity, but much of what was out was pure childish escapism. The stories were often little more than the hero beating up the villain of the month. But as I hit my teens in the 80s, comics started getting a bit deeper. Feelings were explored, character interactions became somewhat more realistic, characters started developing more complicated motivations, etc. And DC instituted the “Suggested for Mature Readers” about the time I graduated High School and started university. DC was struggling to find a way to make reading comics seen as an adult activity. Vertigo was the culmination of that process and came about the time I finished my first degree. So, by the time I was an independent adult, that was the core demographic DC was courting. If DC was still aiming their books at the comics I read in the 70s, it’s possible that I might have lost interest in comics and moved onto “proper adult pursuits” like my mother always hoped I would. So, Vertigo was providing me with the more complex stories I was craving and introduced me to a lot of other comic genres. Although I was a big SF and fantasy fan, I originally didn’t look much beyond the superhero genre, but Vertigo revealed to me that there was a whole world of good comics beyond Superman, Batman, and their compatriots.

Matt: I don’t how much is Vertigo, but I find myself drawn towards characterization as the most critical element in comics and probably fiction in general. It’s what draws me in the most. It’s what I identify with the most. It’s what matters the most. Do characters act consistently? Are they interesting? Do they feel real? Do their relationships with others feel genuine? Are they relatable? Are they likable? Stories driven by characters and relationships.

Kelly: This is going to sound corny, but I love stories that show the importance of doing the right thing. By that, I don’t mean black and white morality tales. I’m talking about stories with damaged, perhaps even evil characters who find themselves in a moment of transformation in which they choose to do the heroic thing. Stories like that give me hope. I’m not saying I’m any sort of demon, but when I’m at a low point, I like to read stories that remind me that change is always a personal choice and always possible. People are crazy- the world is crazy. I think sometimes we need to be reminded not to write ourselves or each other off. We need to be reminded that we all get lost, the world gets dark, and sometimes we lose sight of who we are. That was part of what I loved about Kathy George in Shade the Changing Man. She goes through a life-altering trauma and becomes another person in the aftermath. She loses herself and, somewhat reluctantly, has to go on a ridiculous journey to find what she’s lost. I get a lot out of stories like that. They remind me that I’m a work in progress and that I haven’t lost, so long as I allow myself to change.

As you can see, Vertigo has had a huge impact on us here at DC Comics News, and I’m sure it has affected many of you out there reading this. What is your favorite Vertigo title? How has the imprint had a notable impact on your journey as a comic book fan? Let us know in the comments below!