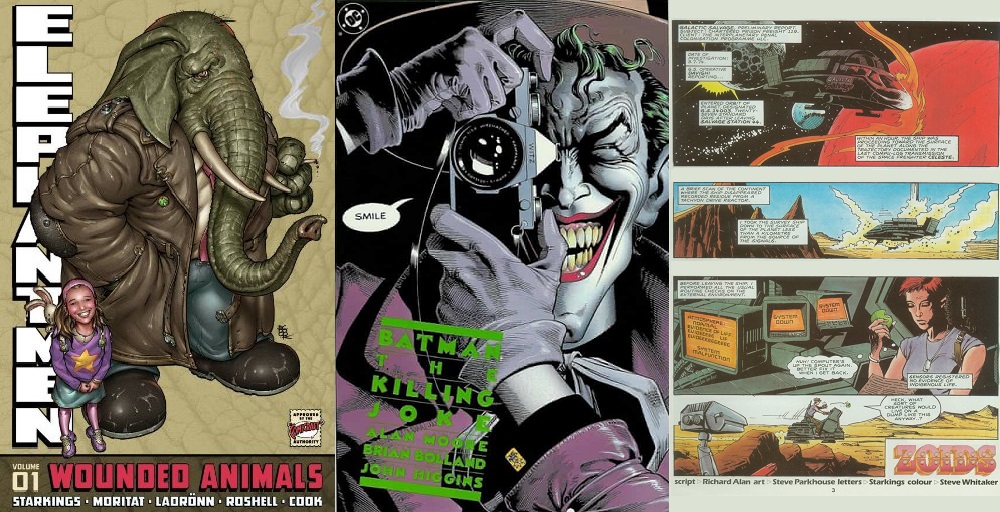

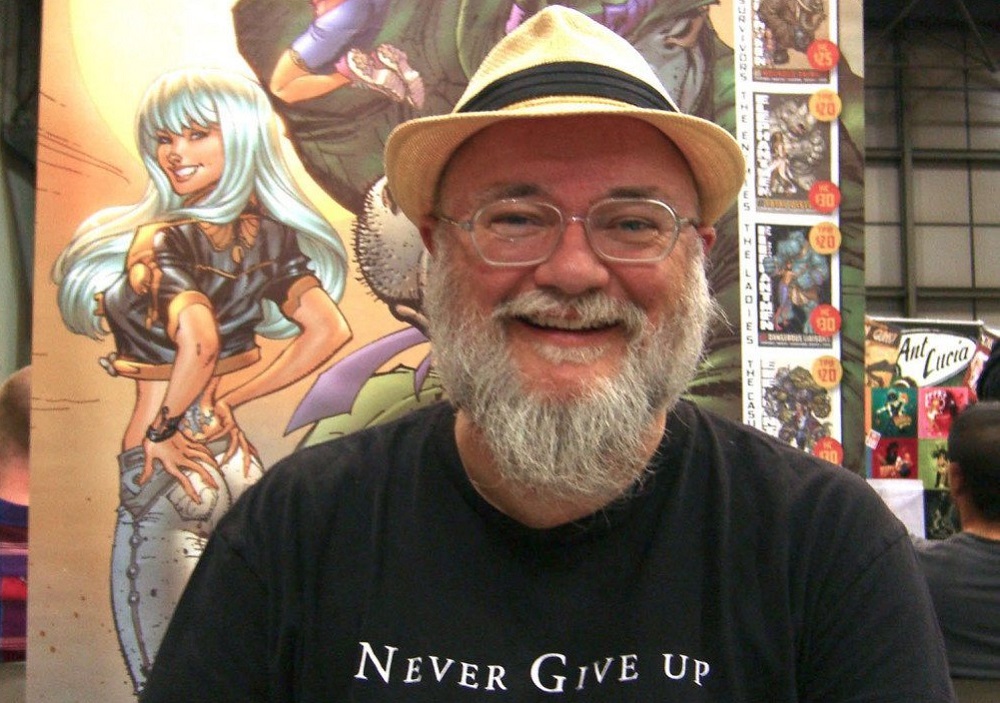

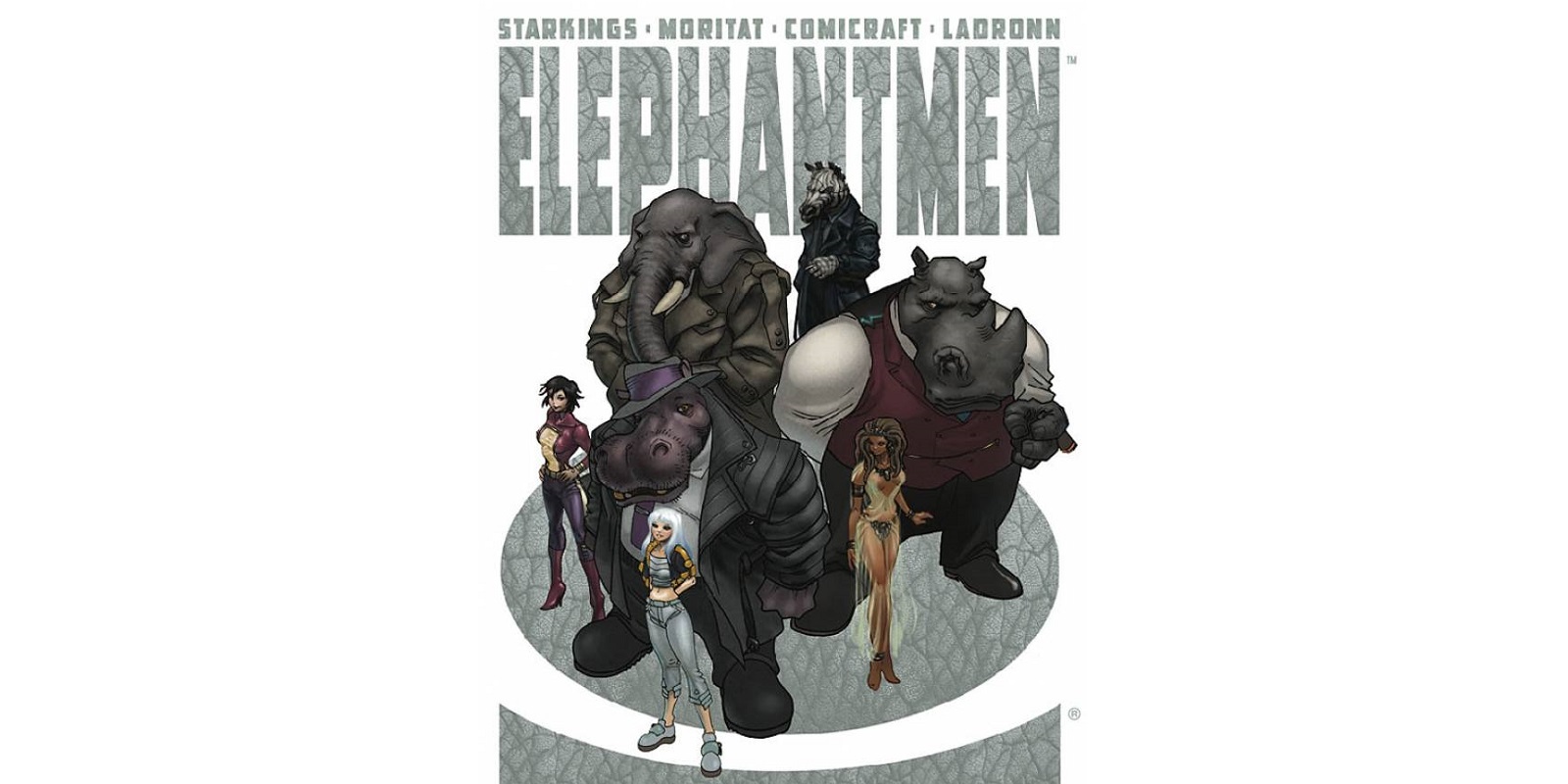

Anyone who’s been reading comics for any length of time will know the name Richard Starkings. He’s the creator/writer of Elephantmen; co-creator, with Abigail Jill Harding, of Ask For Mercy and co-creator, with Tyler Shainline and Shaky Kane, of The Beef.

Anyone who’s been reading comics for any length of time will know the name Richard Starkings. He’s the creator/writer of Elephantmen; co-creator, with Abigail Jill Harding, of Ask For Mercy and co-creator, with Tyler Shainline and Shaky Kane, of The Beef.

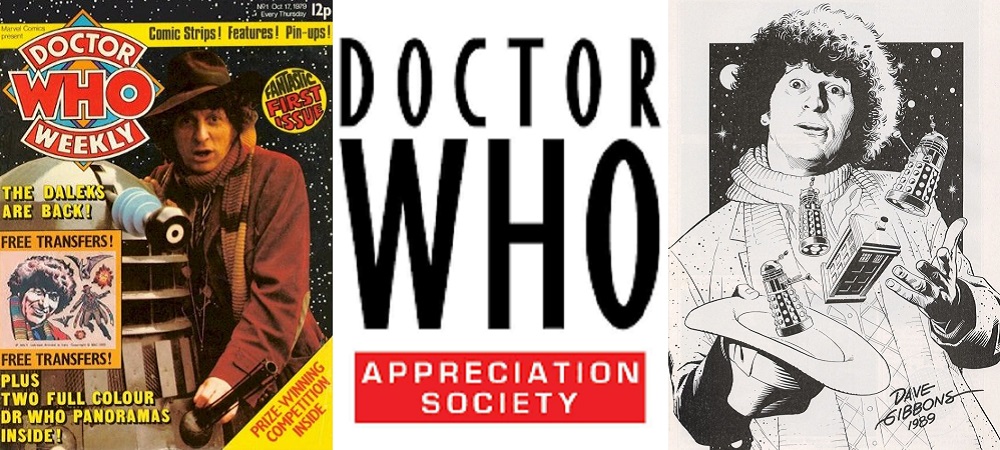

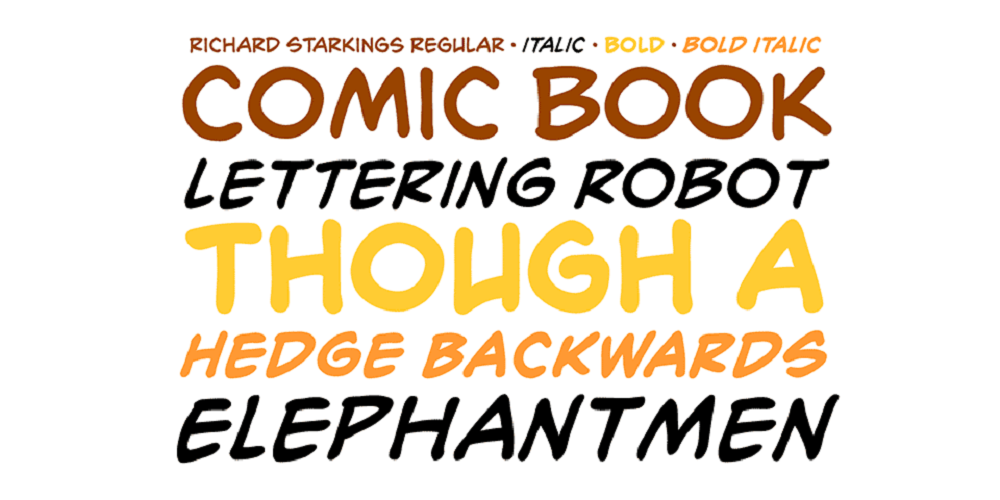

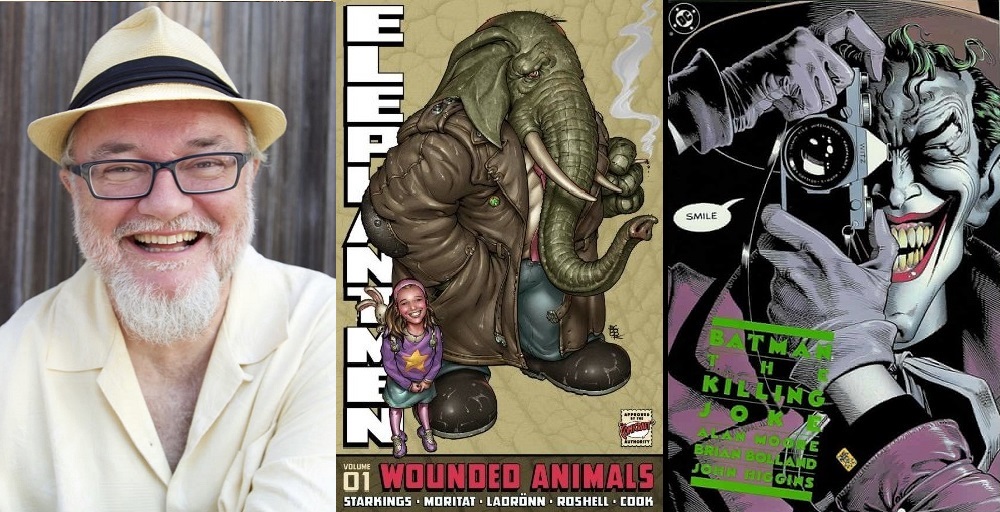

In the course of a distinguished career in comic books, Richard edited a line of original titles for Marvel UK in the 80s, founded the Comicraft design and lettering studio in the 90s, and established the foremost source for comic book lettering fonts at comicbookfonts.com. He’s worked as a lettering artist on just about every mainstream comic book you might care to mention, including legendary books like Batman: The Killing Joke, Batman: The Long Halloween, and Batman: Dark Victory. He’s also written comic strips for The Real Ghostbusters, Zoids, Transformers, and Doctor Who. He and his Comicraft team still letter all the latest Titan Comics Doctor Who books.

He’s one of my heroes as he’s a top-level creative talent, as well as one of the designers and letterers who helped revolutionize the lettering industry. It was a true honor to meet the man and spend an entire hour chatting about his career, his friends and colleagues, Doctor Who, and his clear and ongoing love for the comics industry.

Here’s part one of my exclusive two-part interview. Part two will be presented on our sister site, Dark Knight News.

Richard Starkings

Steve J. Ray: Thanks so much for this. I’ve been a fan of yours since the Marvel UK days, and still am today. Comics in 2021 owe a huge debt to you, and to Comicraft. Let’s not forget that, back in the day, comics lettering was literally dialogue bubbles stuck on acetate over the artwork. You helped launch the digital revolution, as a font designer. You’re also writing comics and have your own creator-owned line.

How did it all start, and why comics?

Richard Starkings: Why comics? Well, I was in a family where I’m the youngest of four. My oldest brother’s 12 years older than me, and he had a massive collection of Marvel and DC comics.

Before he even knew that I was attracted to comics, you know, I was five or six, there was a book called Pippin, which was for very young readers. Then, for me, when Countdown came out, when I was nine in 1971, that blew me away, because it had Doctor Who, U.F.O., and science-fiction.

Richard Starkings: It’s one of those things where I didn’t realize how much I love science-fiction until a friend of mine, Ian Churchill (X-Men, Supergirl) said to me, “You don’t really like superheroes, do you?”, and I said, “I don’t dislike superheroes”, but my favorite superheroes were the Fantastic Four, and they’re very science-fiction oriented.

From there, in later years there was X-Men, which is also very sci-fi oriented… but Countdown was all science-fiction, and I was nine. So that was like, boom! Those were my comics. I think a couple of years later, like ’72, ’73, in order to be on the same wavelength as my brother, I started reading Marvel and DC.

Of course, that was a great way to catch up on all the Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, but unlike most people in England, I had access to complete runs of the main Spider-Man and Fantastic Four comics, because my brother was a dealer… he was a comic book dealer before it was cool. So he had collections, which he constantly upgraded because there was always stuff that he was buying that came through.

In the late seventies, Star-Lord came out. I wasn’t really aware of 2000AD back then, but I loved Star-Lord. Strontium Dog started there, and it was just fantastic.

SJR: I love all the British Anthologies, I came to know your work through the Marvel UK comics. Back in the late 70s and 80s, there was also DC’s The Superheroes, which Egmont published. Again, like yourself, I had older cousins with anthology comics. I remember black and white titles that collected Dick Sprang Batman and Steve Ditko Spider-Man stories in one British comic.

Richard Starkings: Interesting. I was never really a DC guy back then, and one of the reasons for that was my brother’s collection was in a small room in his house in Nottingham and the shelves went from floor to ceiling and he wouldn’t let me go into the DC fifties comics, as they were more valuable than the Marvel sixties comics… back then. So he put them on a shelf I couldn’t reach. So, I could reach all the Marvel comics, which in those days were not as sought-after. So I would literally grab 50 issues of Spider-Man, take them down to his breakfast table, and read them. So that was, for a 10, 11-year-old, you know, to be able to just sit in the summer holidays and read the original Marvel Comics, that was sort of like my idea of heaven.

SJR: So how did you go from being a fan to being a comics pro?

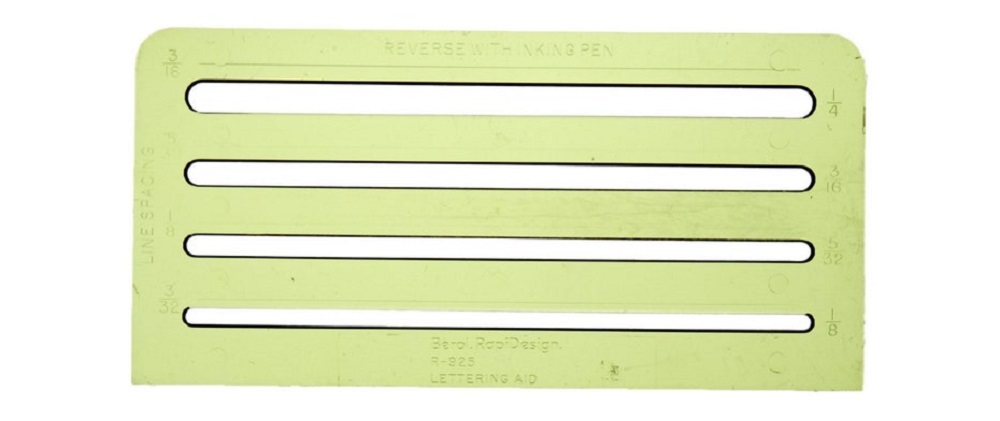

Richard Starkings: I’m a big Doctor Who fan and in the seventies, the Tom Baker era, I drew a Doctor Who strip called Who and Crew, which was published in the Doctor Who Appreciation Society monthly fanzine. I did over a hundred of those stories.

Over time, I did a little collection in the eighties of all the Tom Baker stuff, and that’s where I really sort of taught myself to letter. In fact, in some ways, I was drawing them so that I could letter them. It’s very simple; dots for eyes cartoons. Dez Skinn, back in the day he published three of them in Warrior Magazine because it was that era… the early eighties, I guess.

That’s how I started doing something regularly, you know, and, and I can’t remember now… I think this was monthly, but I would make sure I do at least one comic a month. So I got into that habit of drawing all the time and lettering all the time. I then got a job in London and started going to the Westminster Comic-Marts.

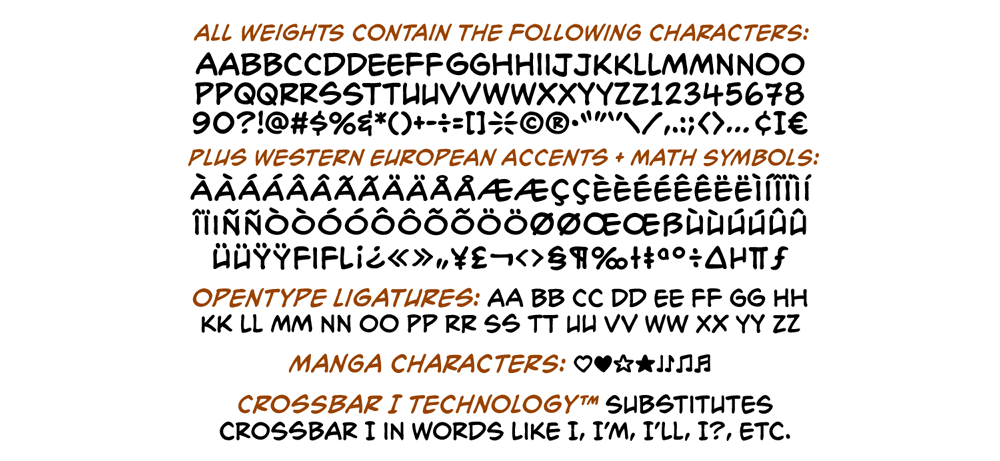

Everybody hung out in the Westminster arms. At that time, you would go into the Westminster arms and it’d be Alan Moore, Brian Bolland (The Killing Joke), Dave Gibbons (Watchmen), Glenn Fabry (Slaine), Steve Dillon (Preacher), Dave Lloyd (V For Vendetta). Dave was the one I went to, and I asked him how to get an aid guide, which is how you rule the lines for lettering.

I can’t remember what year that was, but he told me how to find one, and I started doing little bits of lettering for Harrier Comics, which was a publisher in the eighties. At the Westminster marts, I applied for a job at Marvel UK that was advertised in The Guardian newspaper, and got an interview, but never really a follow-up… and they never hired anybody. So I started doing lettering for Transformers while I was working at a publisher in London. Because I was in and out of the offices once a week, I would stick my head into Ian Rimmer’s office, he was the editor at the time, and I’d say, “Did you find somebody for that position yet?”, and he said, “Come and talk to the managing director”. I started work the next week.

I was doing production on Spider-Man Comics Weekly, which meant doing all the editorial pages, setting up the covers, or the lettering sometimes. That’s the thing, I wanted to get into comics. I didn’t necessarily want to be a lettering artist.

I wanted to work in comics by any means necessary, and I’d read an article in Warrior that said that one of the ways to get into comics was through lettering or design or a production role. Back in the seventies, we didn’t know those roles existed unless you got a job.

I had an English degree that was also partly a design degree. So I sort of fit the right editorial assistant/paste-up artist, that was basically what we called it, but that meant doing design and paste. I continued to do lettering for Transformers. I did a lot of lettering in the day.

I’ve actually been lettering Doctor Who strips for over 30 years. Because I work for Titan now, and I did some for IDW, you know? I wanted my foot in the door and although I started as an art assistant, I became an editorial assistant on Marvel Secret Wars, the UK weekly, and we just had a great team; Ian Rimmer Simon Furman was his assistant.

John Tomlinson worked on Captain Britain and we had a very solid core of people that cared about comics in our department. Within two years I was offered Action Force to edit, and basically from there, worked on Thundercats. What else? Gosh… there were so many titles because they were all weekly.

Ultimately I wanted to work on comics for the American market, so we put Death’s Head in his own book. We did Dragon’s Claws, which was in some ways cynical. We wanted to tap into the 2000AD market, which we all loved. Simon (Furman) came up with that concept. I think our print run was 60 to 80,000 but it was regarded as a failure and was canceled after 10 issues. So, even though we had high print run by today’s standards, Dragon’s Claws closed after ten issues, Death’s Head after ten issues. Sleeze Brothers only lasted six issues.

SJR: I remember Sleeze Brothers!

Richard Starkings: I was working with John Carnell and Andy Lanning on Real Ghostbusters, which was a big hit series that ran like 200 plus issues… that was the most successful thing I launched. John and Andy had lots of ideas and we did a series which was just a gag strip with no real dialogue, just sound effects, and question marks… but they wanted to do this book Sleeze Brothers, which I think they would admit now is loosely based on the Blues Brothers, but at the time they kept saying “No, it’s based on Andy’s cousins”. No, it’s the Blues Brothers and set in the future. We put an issue together and Archie Goodwin was in town for UCAC and… the rest is history.

SJR: To this day, Archie Goodwin is famously known as the nicest man in comics.

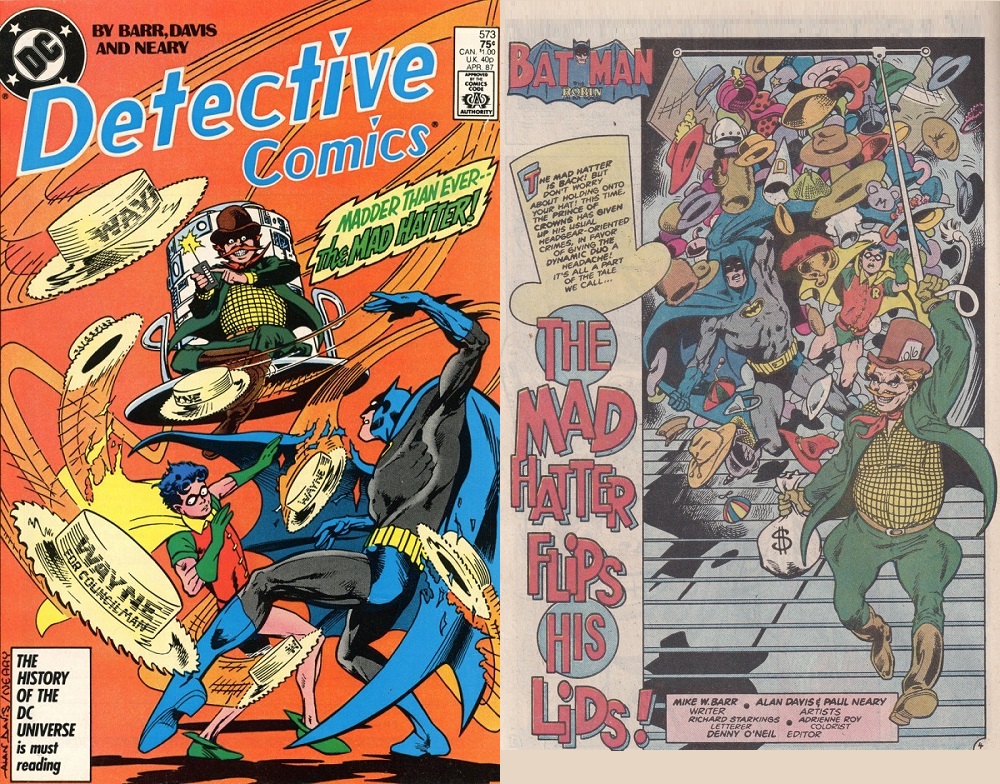

Richard Starkings: He really was. He saw the artwork and said, “If you want this to be an Epic Comics title, I give it my blessing”, and he did. It was the only Epic UK comic book. It was my sort of pet project. Unfortunately, I left halfway through Death’s Head and Sleeze Brothers because I was ambitious, and didn’t see eye to eye with my bosses, but it was just time for me to go. I’d been there for five years. I was doing a lot of lettering for American publishers. By then there were loads of British artists working for American publishers. I’d already done The Killing Joke, and I’d worked on Detective Comics with Alan Davis and Paul Neary.

Richard Starkings: Those were definitely calling cards, so a friend of mine, Greg Wright worked in editorial. I’d got to know him in ’87 and he put me on Avengers Spotlight. I did some Marvel Superheroes, all backups, you know, it was like doing “Future Shocks” for 2000AD… you get little jobs.

Richard Starkings: Then I did Deathlok. It was a mini-series, and my first regular title when I lived in the states. It was always with a view to being in comics, not to make lettering a career, but comics as a career. So that was my four or five years in editorial, so when I decided I was going to stay in America, that’s when I started thinking, okay, I need to pick up regular work.

Let’s just say I didn’t have all the paperwork to live in America in order at the time and it took a little while, but I was working. Because it was a continuation of working freelance for the US publishers in England, I actually had an account that I could pay into in the states.

So I put down roots, got myself a place to live, and developed a freelance career as a lettering artist. That was the early nineties. Then one day I got an issue of the X-Men, and this was the post Image Comics explosion. So a lot of the artists that worked back then got poached by Image, who paid crazy high rates. So, they left and I happened to be there in the right place at the right time.

Richard Starkings: At one point when I was lettering X-Men, my brother was in town and I wanted to spend the day with him. That meant I couldn’t finish an issue and somebody in New York had to do it, and I was kicking myself. I had to ask myself how I could meet the deadlines and also have a life.

So, I knew people from Marvel US that had moved out to the west coast – I was living in Los Angeles at the time – and someone said to me that I should make a font for my lettering. I was like, “Oh, how do I do that?” At the time John Byrne was using a digital lettering font, and I bumped into him at San Diego in the Westgate hotel lobby. I asked him which program he was using, and he told me.

Richard Starkings: I got a job at Graphitti Designs, who at the time were doing t-shirts, hardcover books, prints, and working with a lot of great people. So I was in touch with the California community, and Tom Luth who was the color artist on Groo, had a copy of it, and I think I, we did a trade. I had Adobe Illustrator, he had Fontographer, and back in the day you just traded discs, because you could. There was no way to connect to the internet in those days. So, I learned Fontographer.

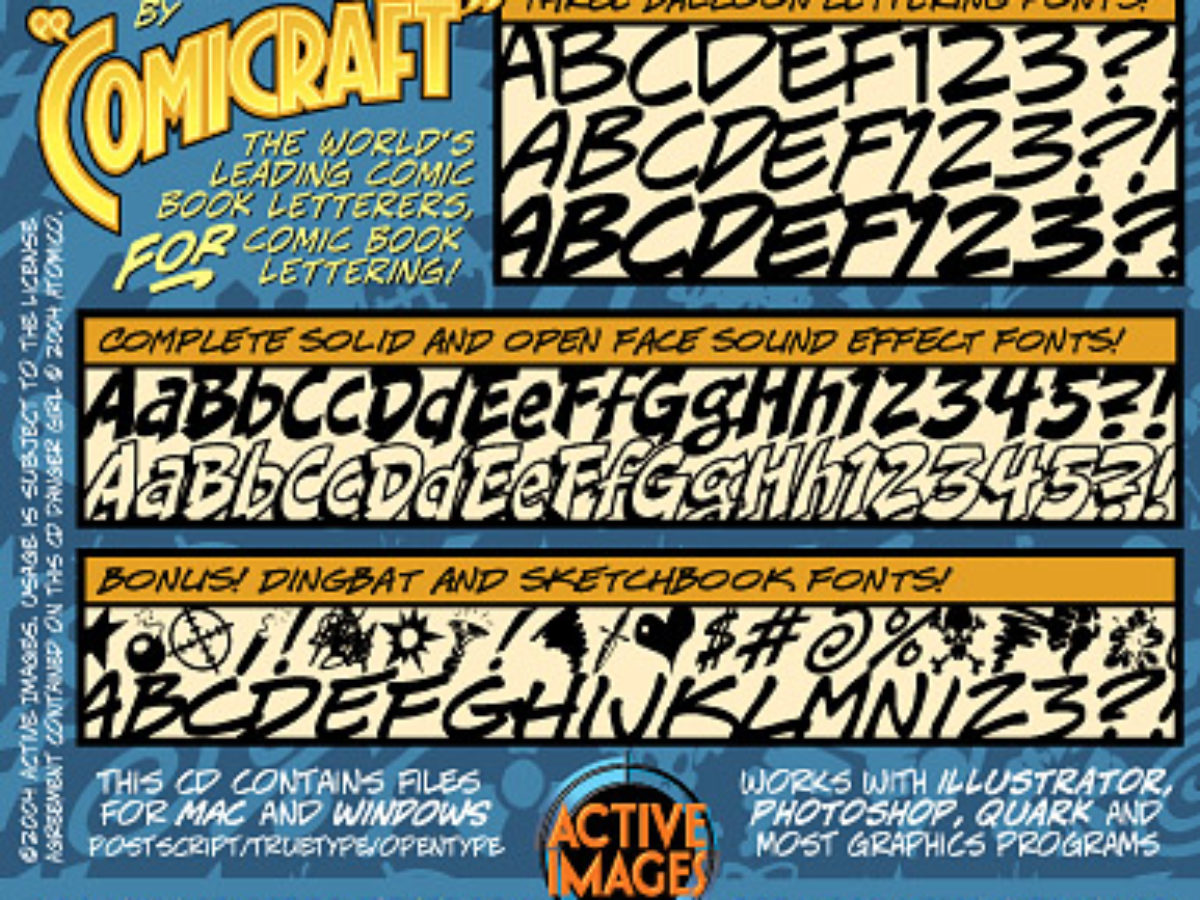

I created my first font and was famously told never to use them on Marvel books. Bob Harras actually called me after he saw that I’d done two pages of X-Factor with an early version of my font. He said, “Richard, you will never use those on X-Men books” because they didn’t look as organic as they do now.

Richard Starkings: Those were the early days. I’d been a bit cheeky and then two pages later knocked them back in. Luckily Greg Wright and Fabian Nicieza said, “Nope, we’re going to let Richard do it this way”, which ultimately gave me a spot. We developed a font over time, and I had hired a guy called John Roshell who took to Fontographer like a fish to water.

Over the course of lettering, Marvels, there are three different versions of my font in that series, you can see its development. Basically what I was doing was trying to make my font perfect. What John did was preserve all my quirks and nuances. Yes, all because he was much more in tune with making digital look like hand-lettering. This is ultimately how I believe fonts should look, you know, much more fluid, more organic.

So that was 1993, ’94. We started working on W.I.L.D.Cats and every spin-off there ever was. Then Astro City… we worked on the expansion of the Spawn line when, when there was like Medieval and Devil-Spawn.

At one point I had a studio in Santa Monica and we were lettering 60 books a month! It was like 70% of Marvel’s output. We were also doing at least 10 books with DC. We were even still doing paste-up hand-lettering at one point; still laying it out, pasting it up. It took a long time and it wasn’t until really the end of the 90s that everything was done as it is today.

Richard Starkings: my idea was always, I wanted to make my own comic book. I wanted to write my own comic book, own my own comic book. write the theme tune, sing the theme tune… I didn’t want to be controlled in the way that the creators I worked with on the Sleeze Brothers, Death’s Head, and Dragon’s Claws were. Although those are owned by Marvel, Sleeze Brothers is owned by John and Andy, because they had an Epic contract. That’s why you’ve never seen a Marvel collection of it.

I had had long conversations with John Wagner and Alan Grant. We used to play Marvel UK versus 2000AD softball, so we used to meet in the park after the game, and would go and sit in a pub at Hyde Park Corner. At the time John was quite bitter because owned nothing on 2000AD. Eventually, there was a change in leadership at Fleetway and they finally gave him a piece of it.

Richard Starkings: Back then though, he was saying, “You know, don’t sell your creations to a publisher”. I read comics during the eighties when Cerebus and Love and Rockets were big. I always think that Elephantmen is actually Cerebus and Love and Rockets in one book. Dave Sim and Jaime Hernandez were doing creator-owned comics, they owned what they made. There was a lot of talk about that in the eighties and it’s taken for granted now that you can create something and own it. Obviously, it’s still in the news because of the Marvel movies, Bill Finger, Jack Kirby. These were all creators who didn’t get a substantial reward for their contribution to the industry.

I never wanted to be in that situation. I love Batman but never wanted to write it… I say never because I sort of scratched that itch by working on it as a lettering artist. Of course, that doesn’t reward you either. You do not get a royalty. It’s horrible. Writers and artists get healthy royalties, some colorists have negotiated royalties. So John Higgins, I think, I believe finally got a royalty fee on the Killing Joke for his colors. I don’t, but I didn’t negotiate that. At the time I don’t think I could, but I have had royalties for Grendel Prime.

Richard Starkings: I’ve also had royalties for Astro City and some generous creators have given me kickbacks out of the kindness of their hearts. I do get royalties from selling fonts. So that’s sort of the ultimate, it’s creator ownership. John Roshell and I own the font line, we created it together and we benefit from it.

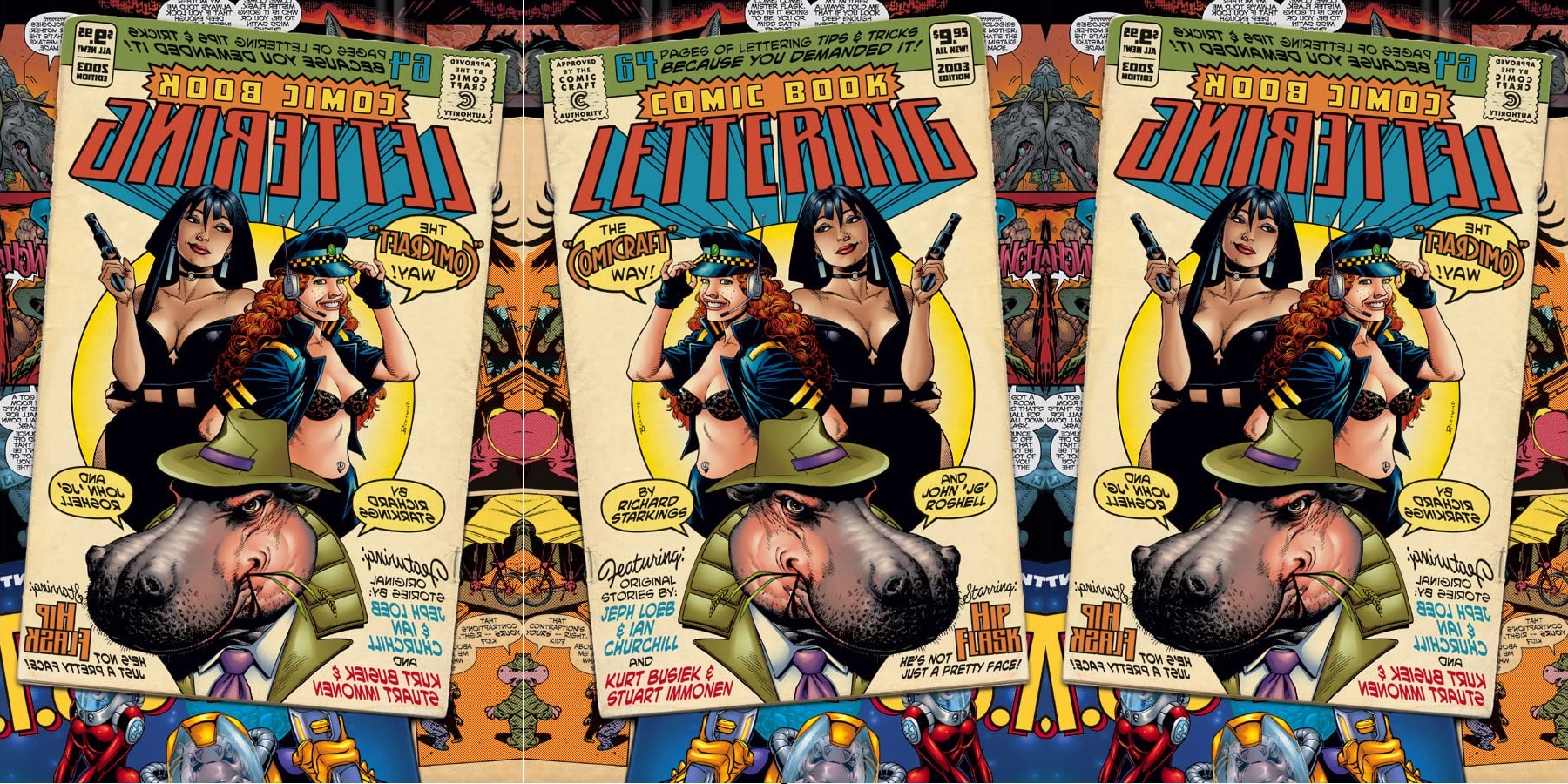

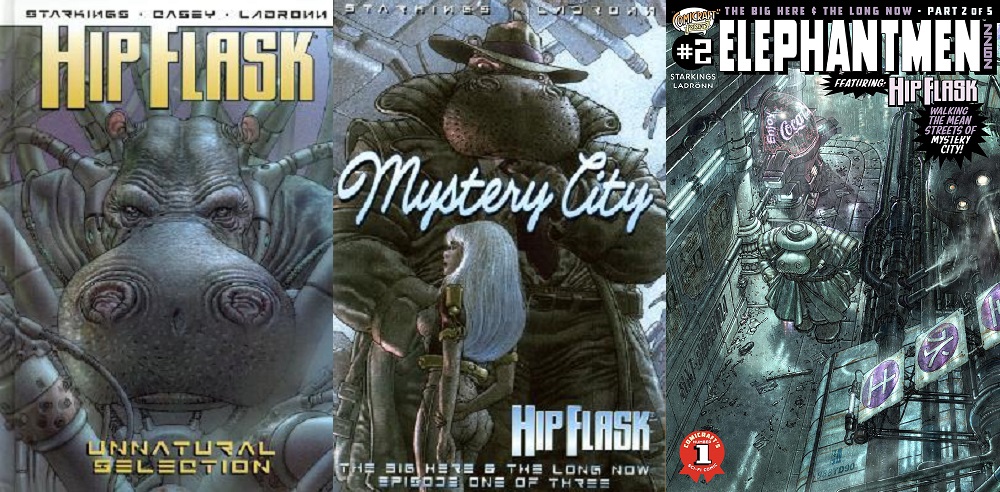

This was always done with the idea of bankrolling my own comic book, which ultimately was Hip Flask, which then led to Elephantmen.

SJR: Let’s talk about those. Let’s talk about all your work with comiXology and with Image. Now you’re creating your own comics. They’re yours and they’re great, so let’s tell new readers all about them.

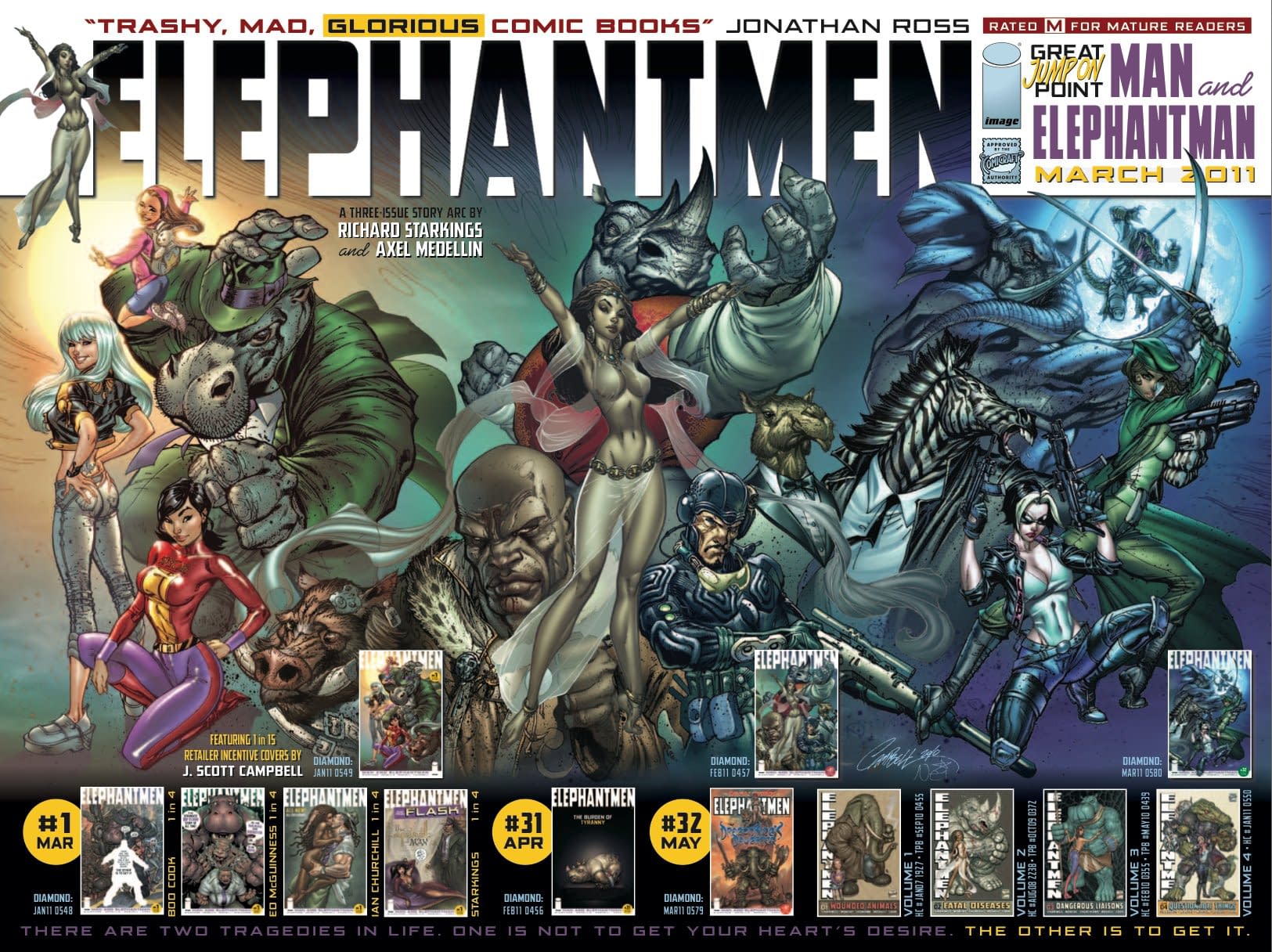

Richard Starkings: Well… Elephantmen was going to be… I thought if I could write something, I maybe had four issues in me. I could maybe write one story. Ironically, that first series was a five-issue series created 22 years ago. What happened is Ladronn hasn’t yet finished, because he went and did The Incal for a few years.

The good news is that he’s actually working on it this year and we will finally finish that five-issue series. I wrote that story in 1999, and the script is only now wrapping up.

When Image approached me to publish Hip Flask, I was like, well, I can’t work on a monthly with Ladronn, as he’s so methodical. The plan was to follow it up with a Hip Flask sequel set in 2262. So I thought to let him finish the first series, and I’d start a prequel instead, and by the time he finished Hip Flask, I could then do the sequel. I thought I’d get maybe 10, or 20 issues into Elephantmen, and he’d finish Hip Flask. Luckily I set it in 2259, 3 years before, because I’ve since done a hundred issues of Elephantmen that are all the prequel to Hip Flask!

Richard Starkings: When it’s concluded, which should be next year, I will have done 105 prequel issues. This can be frustrating cause you can’t kill any characters. You can’t really resolve any stories that clearly aren’t resolved in the Hip Flask story. Thankfully, it’s all been very satisfying, and I taught myself how to write an ongoing series. Anyone who’s done an ongoing series will tell you it isn’t easy when you’re the sole writer, especially for over a hundred issues!

The story we’re doing right now leads right into Hip Flask, but it’s interesting, I may be exhausted, but I thought I was exhausted when we finished issue 80 with Image. I always thought it’s 60 to 80 is about right, you know? I think Sandman was 75 issues. So, 10 volumes, 10 trades, um, so that, you know, it sits on the shelf. You can do omnibuses and you’re not losing your audience.

Head on over to Dark Knight News for part two of this interview, where Richard talks about The Killing Joke, The Long Halloween, and more!

Images May Be Subject To Copyright. Photos by Jessica Cole Eriksen and Luigi Novi.